Kanji Stroke Order Guide

How to write Japanese characters

Welcome to my Kanji Stroke Order Guide, or 漢字筆順ガイド kanji hitsujun gaido.

This guide is intended to be an easy to read resource on how to write 漢字 kanji, also known as “Japanese characters” or “Chinese characters”.

Preface

Kanji should be written with a rapid, confident movement of your hand. Ideally, you should never stop and think: “what is the right way of writing this character?”.

With the help of this guide you will be able to achieve a solid understanding of the principles that are at the basis of kanji stroke order.

For many reasons, it is very important to know the correct stroke order of each kanji. It’s not something you should ignore or leave to your imagination.

Reasons are mostly practical. If you don’t know the correct stroke order:

- you will never learn to read cursive Japanese;

- learning kanji will become a lot more difficult and time consuming.

If you are studying kanji, don’t lose the opportunity to learn them with the correct stroke order.

Stroke order looks like a chaotic mess, but it’s a lot easier than you think. It’s a little like riding a bicycle: difficult at first, automatic at last.

In writing kanji with their correct stroke order there are:

- clear rules;

- clear exceptions to those rules;

- some arbitrary rules applied on a case-by-case basis.

That’s it! Your objective is to commit these rules and exceptions to muscle memory. Having achieved that, no actual thinking should ever become necessary again.

Regarding the arbitrary rules: learn them as you encounter them. Same shapes follow same rules, which means that once you learn an unusual stroke order, you will be able to apply it to all the characters where that shape appears.

In this guide I want to provide a good foundation for points 1 and 2, and an overview on point 3.

We will learn about the three dimensions of kanji composition in 20 intuitive rules:

- Stroke direction -> 4 rules.

- Stroke order -> 10 rules.

- Component order -> 6 rules.

Some of the concepts presented here are my personal and original view of what an interpretation of the rules that govern kanji writing could be. I am open to suggestions that can lead to an improvement of the current guide.

Notes

This guide is available entirely for free on:

The font that I used in this guide is:

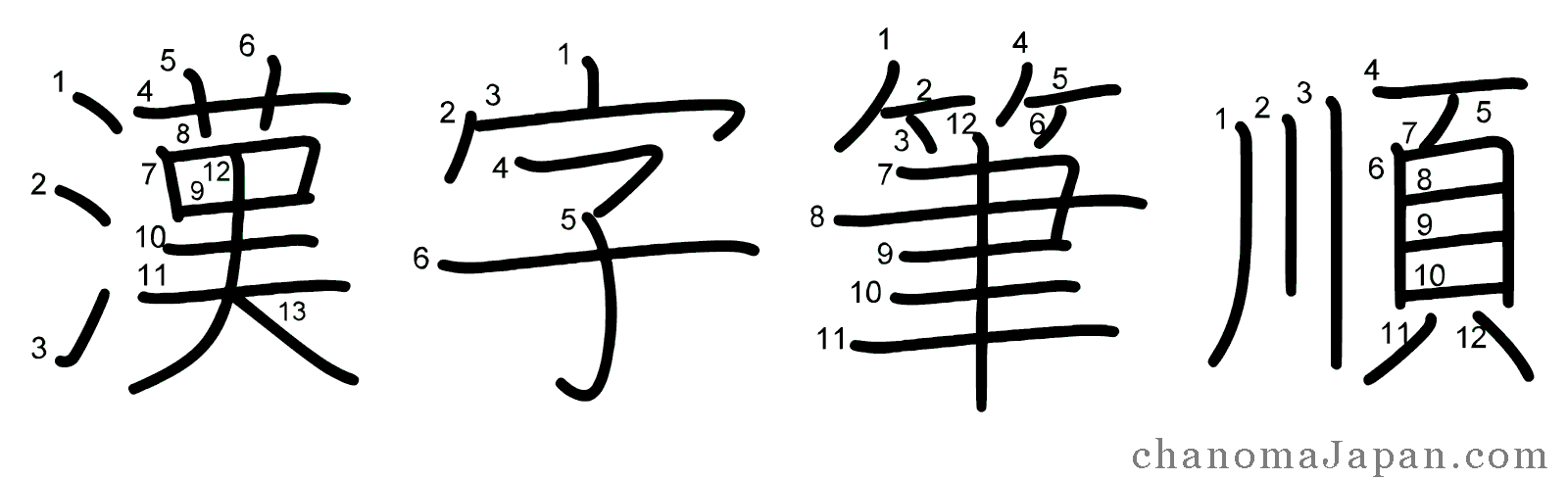

- the Kanji Stroke Order Font, a.k.a. 漢字の筆順のフォント kanji no hitsujun no fonto.

The colour scheme used in this guide is colour blind friendly, and black&white photocopy friendly. I will refer to the colours as green, brown, red and blue (and black, where present).

The top row shows the colour scheme. From left to right: green, brown, red, blue. The bottom row shows the same colour scheme in greyscale (black&white).

Introduction: How to Read Stroke Diagrams

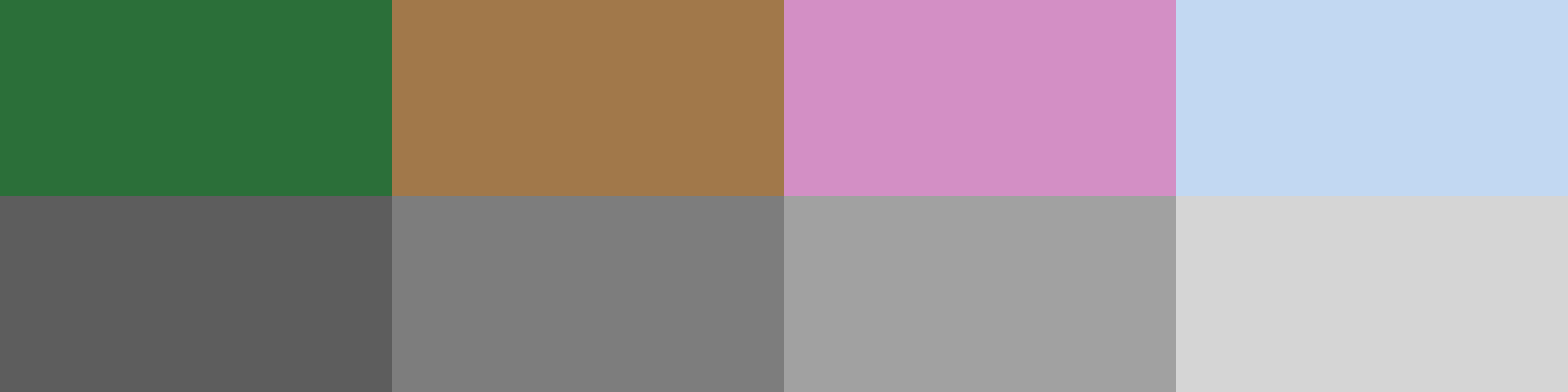

Observe the character for ‘love’, 愛 AI, in the stroke diagram below. As you can see, ‘love’ is made up of 13 strokes.

The small numbers next to each stroke are telling us two things:

- the direction of the stroke, and

- the order of the stroke.

Stroke direction is easy. Each stroke has, quite logically, two extremities:

- The extremity where the stroke starts, and

- the extremity where the stroke ends.

Stroke order is easier: write the strokes one by one, from the first one to the last one. In this case, from stroke 1 (red) to stroke 13 (red).

A stroke starts where your pen first touches the paper, and ends where you lift the pen from the paper.

The small numbers are located as close as possible to the extremity where the strokes start. For example, in the character above:

- The 6th stroke (green) starts at the left extremity, and ends with a downward hook at the right extremity.

- The 9th stroke (green) is a very short diagonal stroke which is written with a descending motion, ending with a tiny hook toward the right. The whole character resembles a small ‘L’ shape.

- Again, the 12th stroke (green) starts from the top, where the small ‘12’ is situated, then moves horizontally toward the right, changes direction once, and descends diagonally toward the left.

In the next section we are going to learn the very basics of how to write kanji: the stroke direction rules.

Stroke Direction (4 Rules)

In this section you should focus solely on the stroke directions indicated by the small arrows (where present), and ignore everything else. If the direction is not clearly indicated by arrows, it will be fairly easy to figure it out thanks to the small numbers situated where each stroke starts.

We are now studying the direction of strokes, not their order.

There are 4 stroke direction rules.

- Stroke direction rule 1: left to right.

- Stroke direction rule 2: top to bottom.

- Stroke direction rule 3: nisui rule (pron. /nee-soo-ee/).

- Stroke direction rule 4: tehen rule.

SD rule 1: left to right

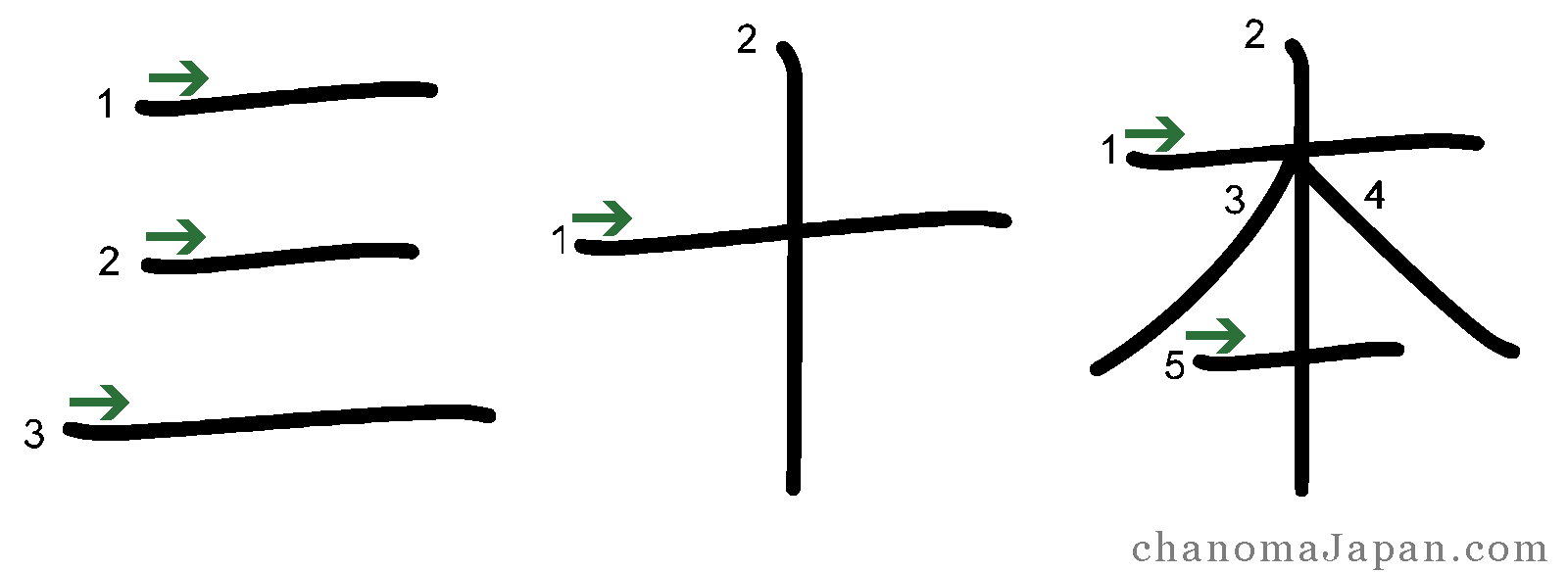

Horizontal strokes are written from the left to the right. Let’s see the character for ‘one’ (as in ‘number one’), 一 ICHI.

The image above shows the three stages of writing the kanji 一 ICHI, which is a simple horizontal stroke:

- touch the paper with the pen,

- move the pen toward the right, and

- lift the pen from the paper.

Now observe the three characters below.

Can you see how all the horizontal strokes are written left to right? If you learned how to read stroke diagrams in the introduction to this guide, you will remember that the small numbers are placed where the strokes begin.

The first character is 三 SAN ‘three’. Its three strokes are simple horizontals, and they are written left to right according to rule 1. Notice how the small numbers ‘1’, ‘2’ and ‘3’ are situated on the leftward extremity of each stroke?

The small numbers are telling us that the strokes start from the left and proceed toward the right.

The second character is 十 JŪ ‘ten’. Only one of its two strokes is horizontal; it is obviously written left to right.

The last character is 本 moto ‘origin’. Two of its five strokes are horizontal strokes, and they are written from the left to the right. You get the idea.

SD rule 2: top to bottom

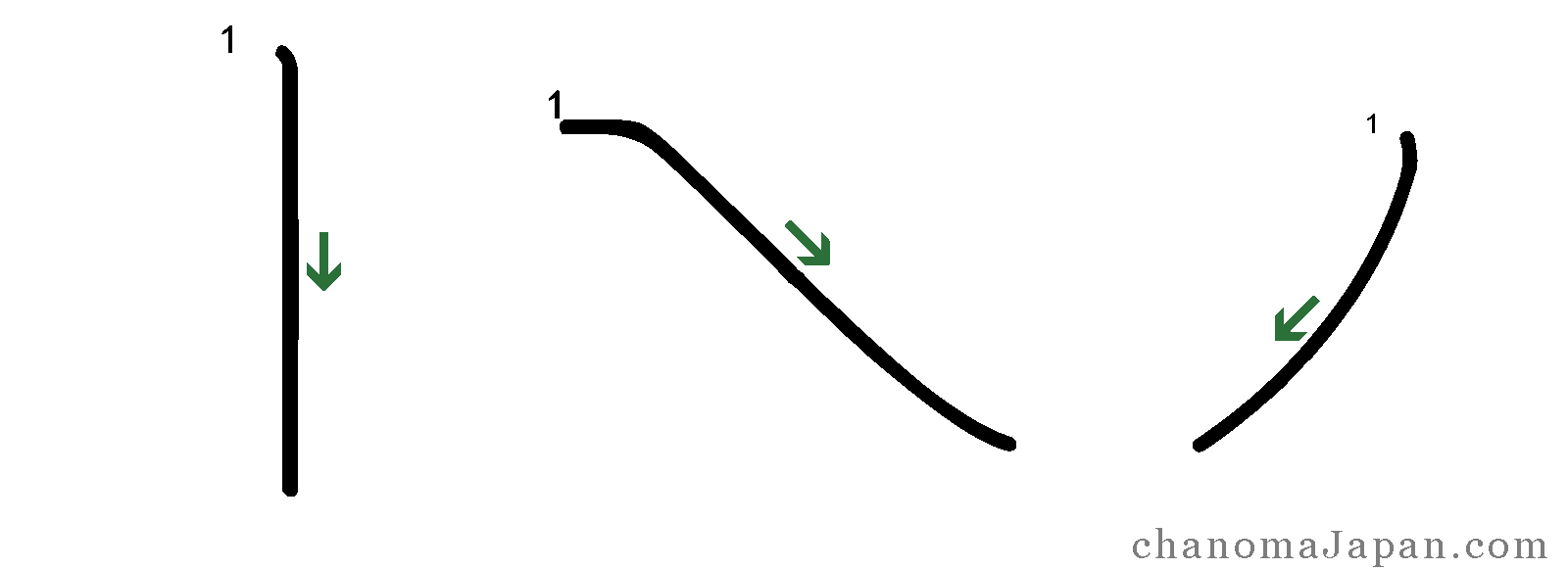

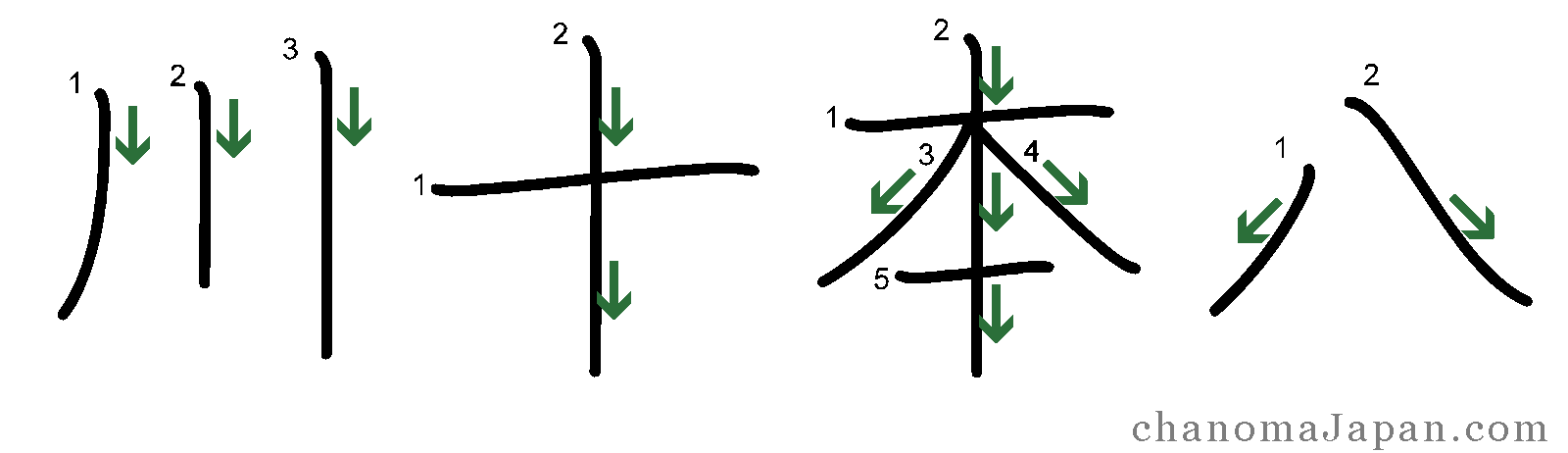

Vertical and diagonal/slanted strokes are written with a downward motion: from the top to the bottom.

Let’s see 川 kawa ‘river’, 十 JŪ ‘ten’, 本 moto ‘origin’, and 八 HACHI ‘eight’. This time focus on the vertical and slanted strokes.

The image is self-explanatory. The small numbers indicate the extremities where the vertical and slanted strokes start, and in each case the strokes are written top to bottom.

Apparent exceptions

Sometimes you will encounter other shapes that seem to contain diagonal/slanted strokes that are written bottom to top. They may seem like exceptions to stroke direction rule 2, the top-to-bottom rule, but they are not.

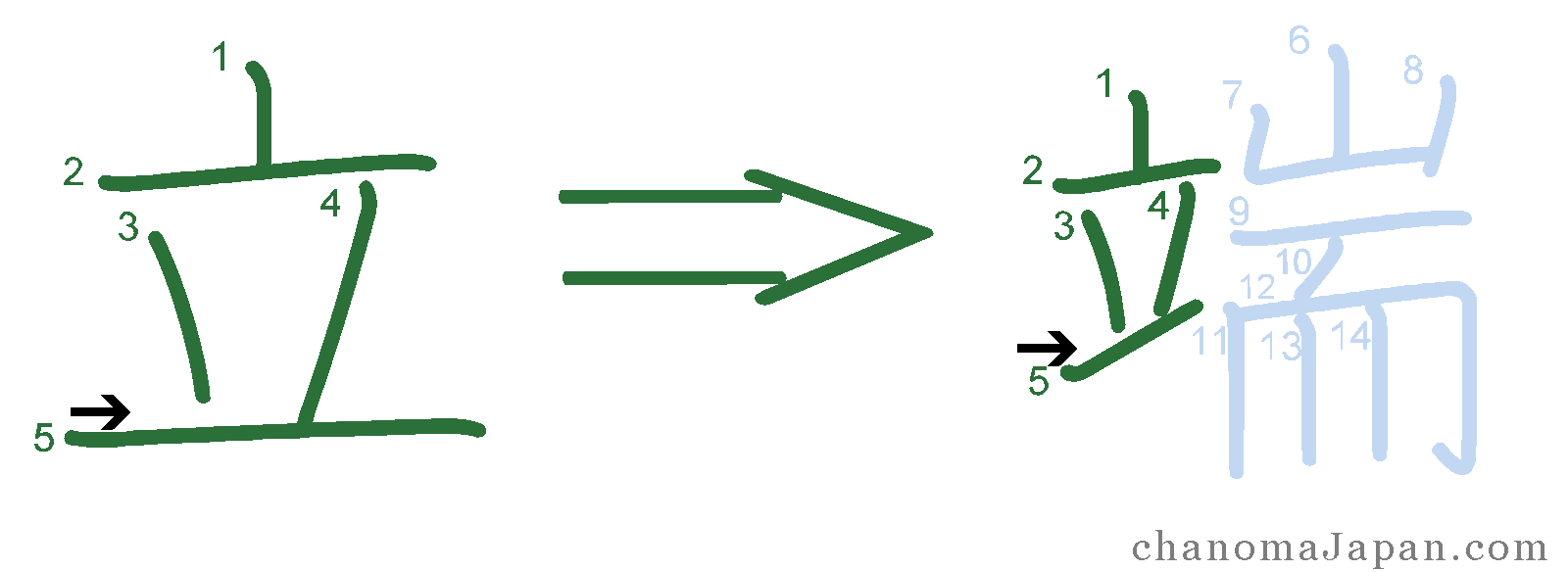

In the image below, the fifth stroke of the kanji 端 hashi ‘edge’ is remarkably slanted, but it is written left to right, as verifiable on any kanji dictionary.

The reason is that the left component of 端 hashi is in fact 立 tatsu ‘to stand’. What looked like a short diagonal stroke in 端 hashi, is in fact a long horizontal stroke in 立 tatsu.

The shape 立 tatsu within the kanji 端 hashi inherits the stroke direction of 立 tatsu.

In 端 hashi, the fifth stroke is made to look slightly slanted for stylistic reasons.

When a kanji is made up of two components as in 端 hashi, the lowermost horizontal stroke of the left-hand component often becomes markedly slanted in order to preserve balance in the overall shape of the character.

Here I present more kanji where the same stylistic principle applies.

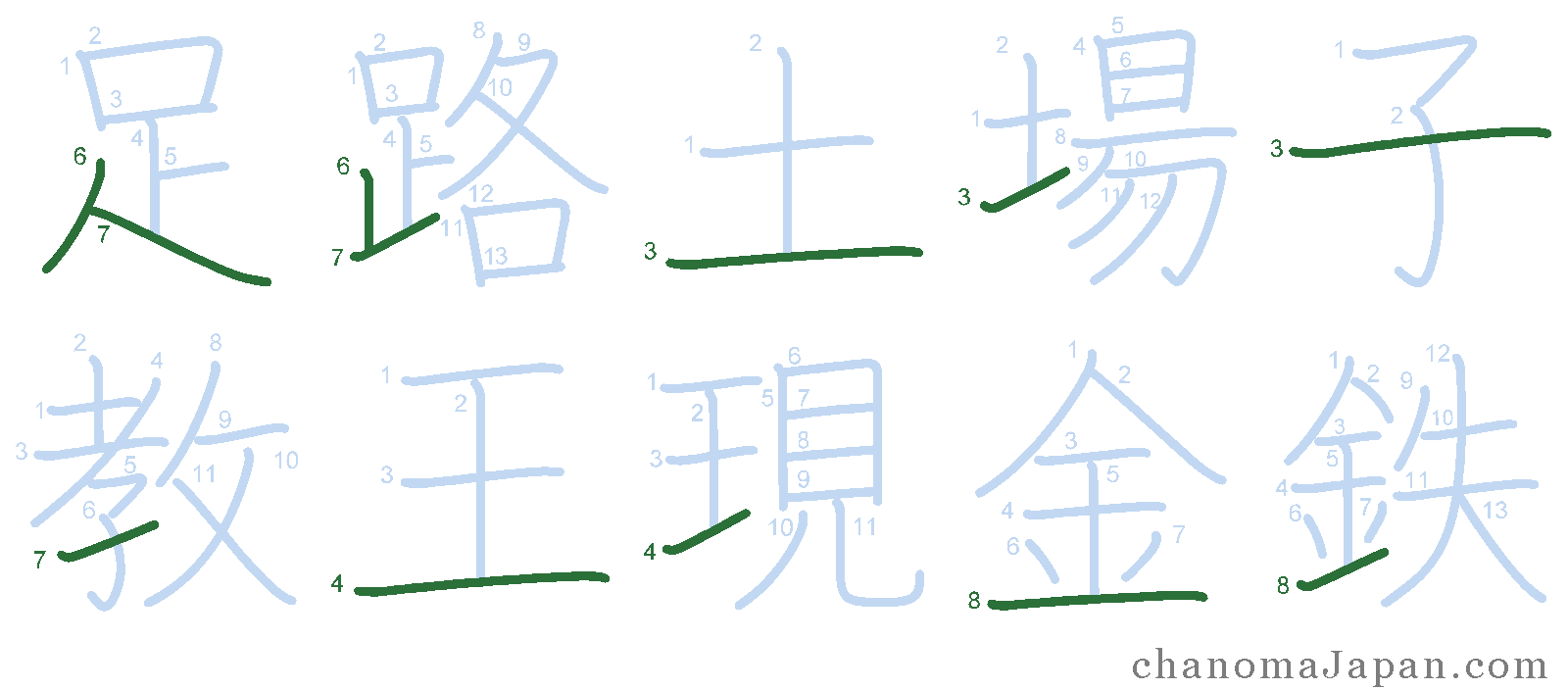

In the image above: 足 ashi ‘leg’, 路 ji ‘road’, 土 tsuchi ‘earth’, 場 ba ‘place’, 子 ko ‘child’, 教 oshieru ‘to teach’, 王 Ō ‘king’, 現 arawareru ‘to appear’, 金 KIN ‘gold’, 鉄 TETSU ‘iron’.

This kind of thinking requires a basic level of kanji knowledge. For instance, if you already know the characters 足 ashi, 土 tsuchi, and 王 Ō, then you will instantly recognise them when they act as components within the structure of other kanji like 路 ji, 場 ba, and 現 arawareru.

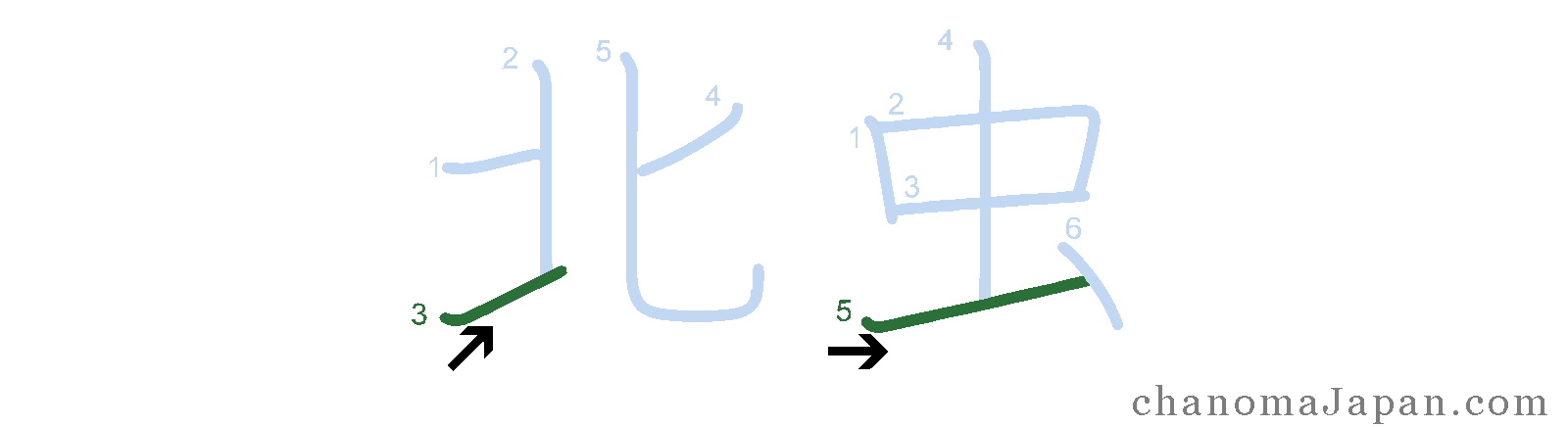

I have identified two less obvious kanji where a stroke that looks slanted is written left to right: they are 北 kita ‘north’ and 虫 mushi ‘insect’. We can easily memorize these.

SD rule 3: nisui rule

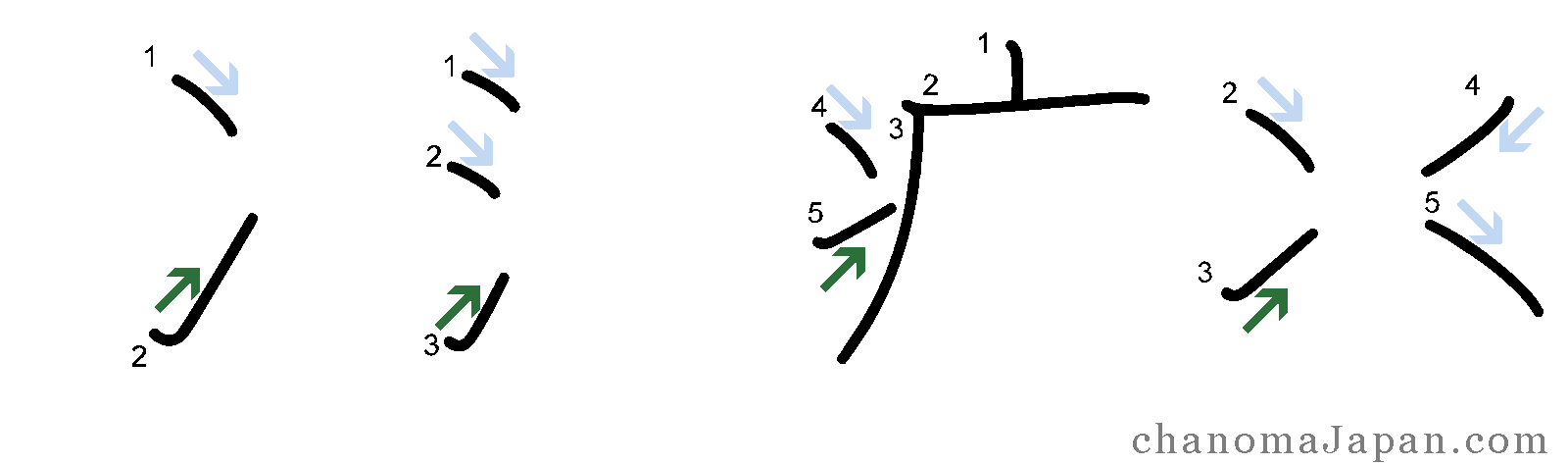

This rule expresses an exception to the top-to-bottom rule. The exception is found in the 冫 nisui shape (pron. /nee-soo-ee/). The nisui rule states:

- The lower stroke in the 冫 nisui shape is written from bottom to top.

The following shapes also contain the 冫 nisui shape:

- 氵 sanzui,

- 疒 yamaidare, and

- the four short symmetrical strokes in characters like 求 motomeru.

In the shapes above, the green arrows highlight the nisui rule, while the light blue arrows show the strokes which are written normally, ie according to stroke direction rule 2: the top-to-bottom rule.

Fundamentally, the four shapes we have just seen are just variants of the simpler 冫 nisui shape. The only thing that you have to commit to muscle memory is:

- the lower stroke in the 冫 nisui shape is written bottom to top.

Practice writing this shape.

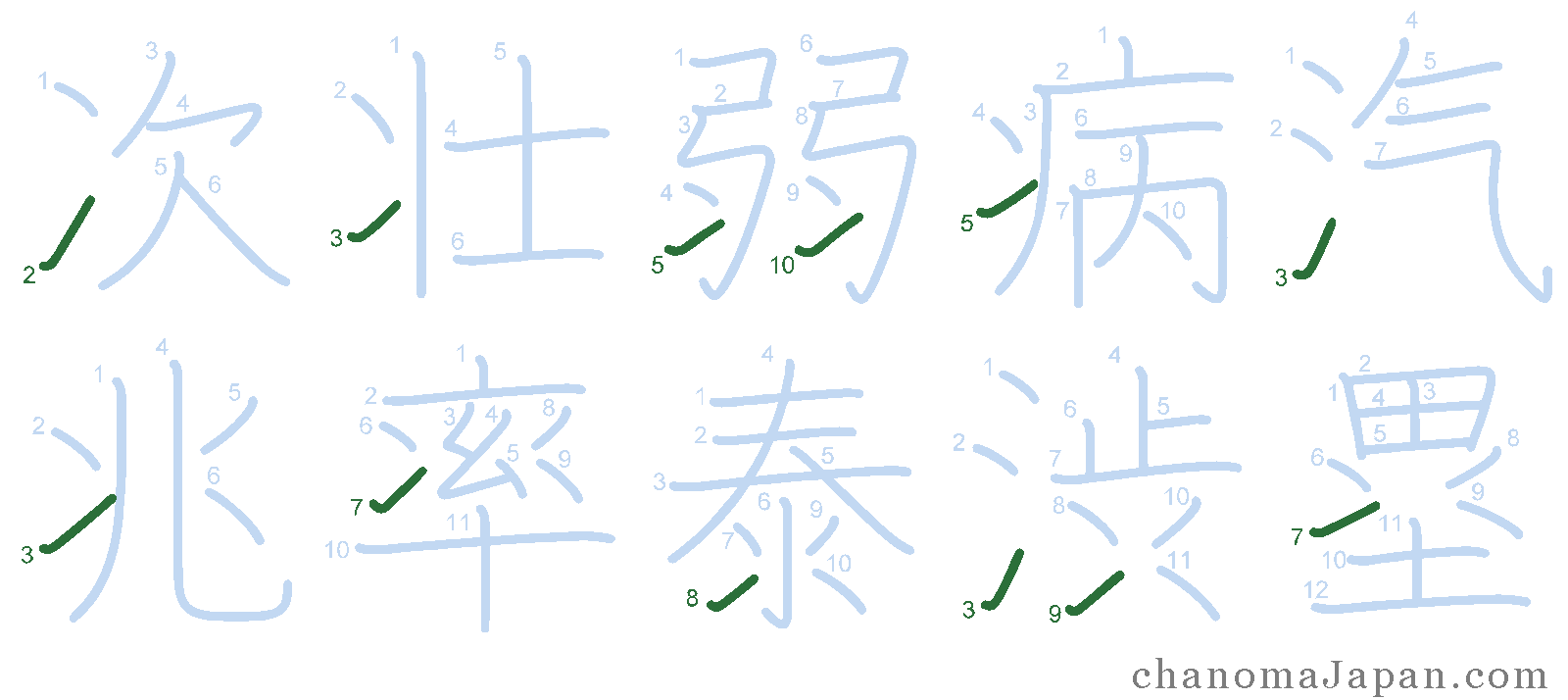

In the image above I present twelve kanji containing the 冫 nisui shape. The kanji are: 次 tsugi ‘next’, 壮 SŌ ‘vibrant’, 弱 yowai ‘weak’, 病 yamai ‘illness’, 汽 KI ‘vapour’, 兆 kizashi ‘omen’, 率 hikiiru ‘to lead’, 泰 TAI ‘peaceful’, 渋 shibui ‘bitter’, 塁 RUI ‘base’.

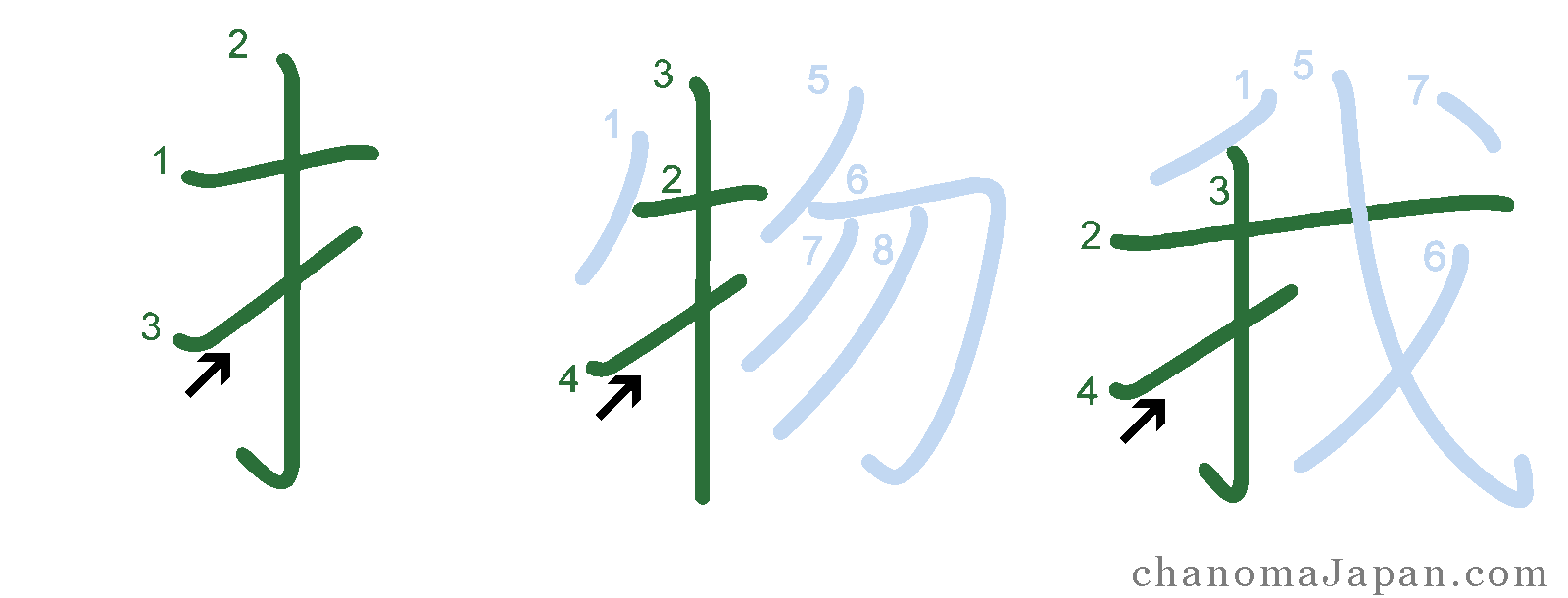

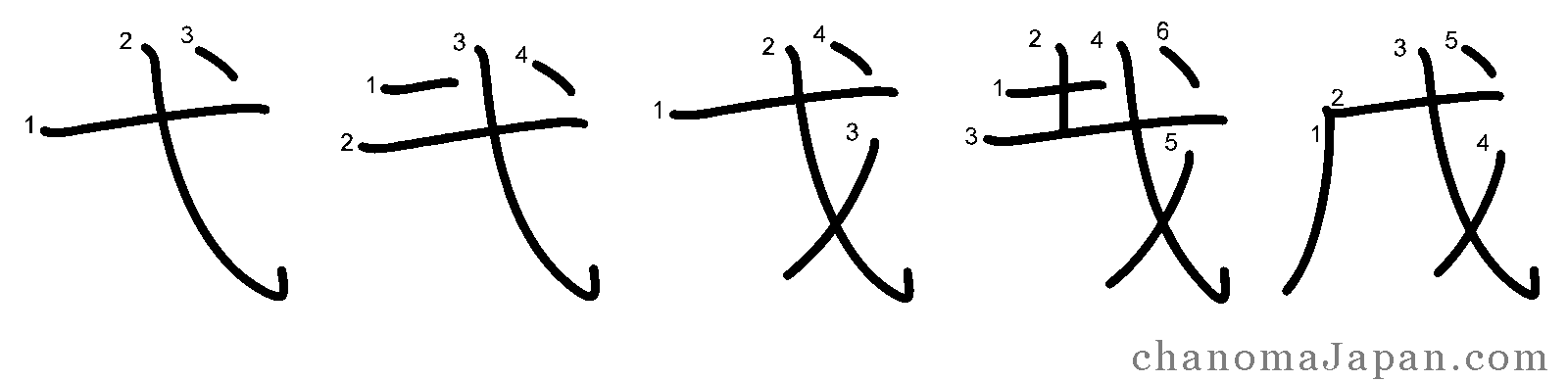

SD rule 4: tehen rule

The 扌 tehen ‘hand’ shape contains a diagonal stroke that is written from the bottom to the top, thus constituting another exception to stroke direction rule 2.

The tehen rule states:

- the third stroke in the 扌 tehen shape is written bottom to top.

Below, the leftmost character is 扌 tehen, which is the pictogram of a hand. As clearly indicated by the arrow, the diagonal stroke is written with an ascending motion: bottom to top.

Above, the same 扌 tehen shape is included in the shape 牜 ushihen ‘cow’, and also in the character 我 ware ‘myself’.

Do not mistake the 扌 tehen shape for the kanji 才 SAI ‘ability’, which is an entirely different shape and character.

Below, the direction of the diagonal stroke in 才 SAI (third stroke) follows stroke direction rule 2: the top-to-bottom rule!

The diagonal stroke in 才 SAI is a perfectly normal stroke, and should follow the top-to-bottom rule. This is simple enough.

This type of shape-based knowledge will become common sense soon enough. All you need is a certain degree of familiarity with Japanese characters. For now, keep in mind that 扌 tehen and 才 SAI are separate shapes, and have nothing in common with each other.

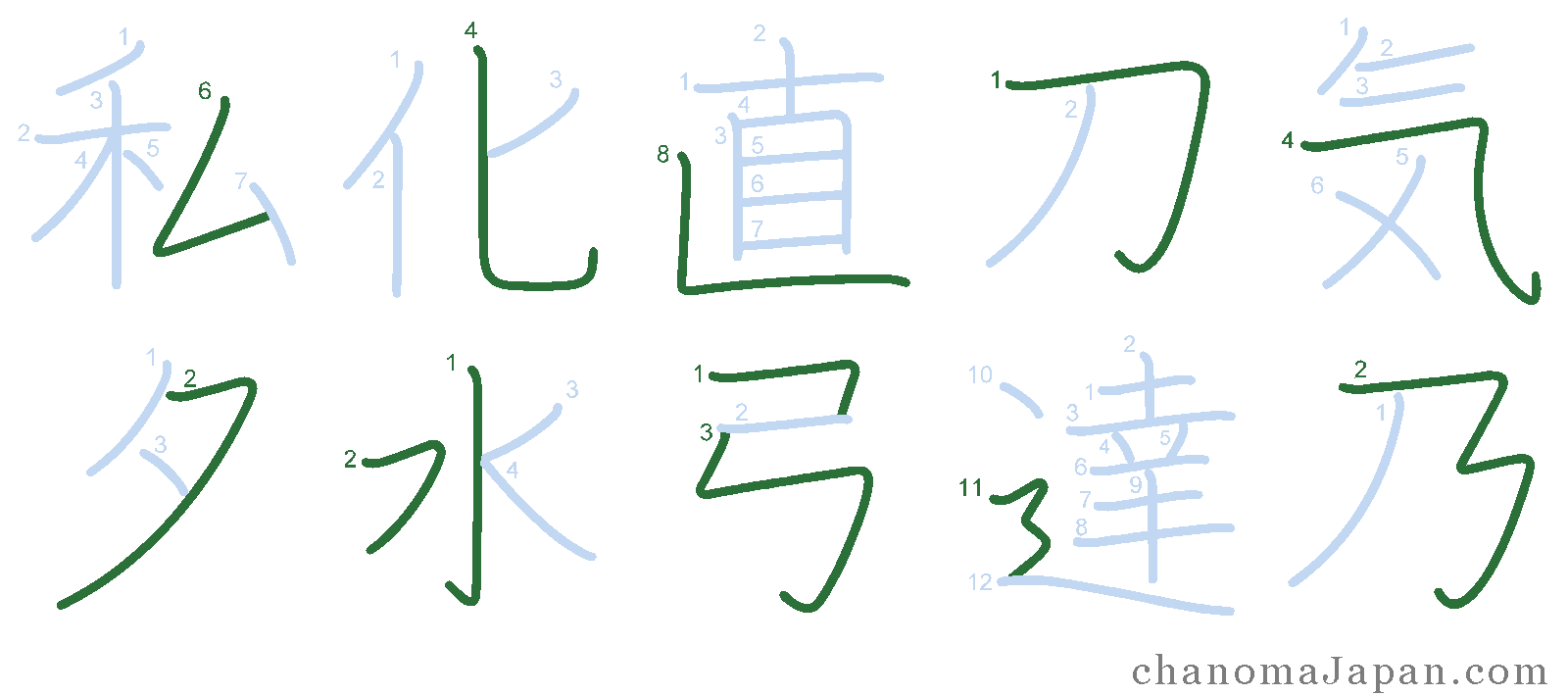

Change in direction

A single stroke can change direction once, twice or several times. Observe the highlighted strokes in the following characters: 私 watashi ‘I’, 化 bakeru ‘to mutate’, 直 naosu ‘to adjust’, 刀 katana ‘sword’, 気 KI ‘spirit’, 夕 yū ‘evening’, 水 mizu ‘water’, 弓 yumi ‘bow’, 達 TATSU ‘to reach’, 乃 no (grammatical particle).

Strokes that change direction are not special: they follow the same direction rules like every other stroke. You should write them left to right (stroke direction rule 1), and top to bottom (stroke direction rule 2), or:

Stroke Order (10 Rules)

Until now we have been talking about the direction of strokes.

Now we will start talking about the order/sequence in which multiple strokes should be written to form a whole kanji.

In this section we will learn the 10 stroke order rules.

- Stroke order rule 1: left to right.

- Stroke order rule 2: top to bottom.

- Stroke order rule 3: droplet last.

- Stroke order rule 4: crossing horizontal first.

- Stroke order rule 5: prominent middle first.

- Stroke order rule 6: piercing horizontal last.

- Stroke order rule 7: piercing vertical last.

- Stroke order rule 8: hidariharai first.

- Stroke order rule 9: horizontal vs hidariharai, short first.

- Stroke order rule 10: long crack first.

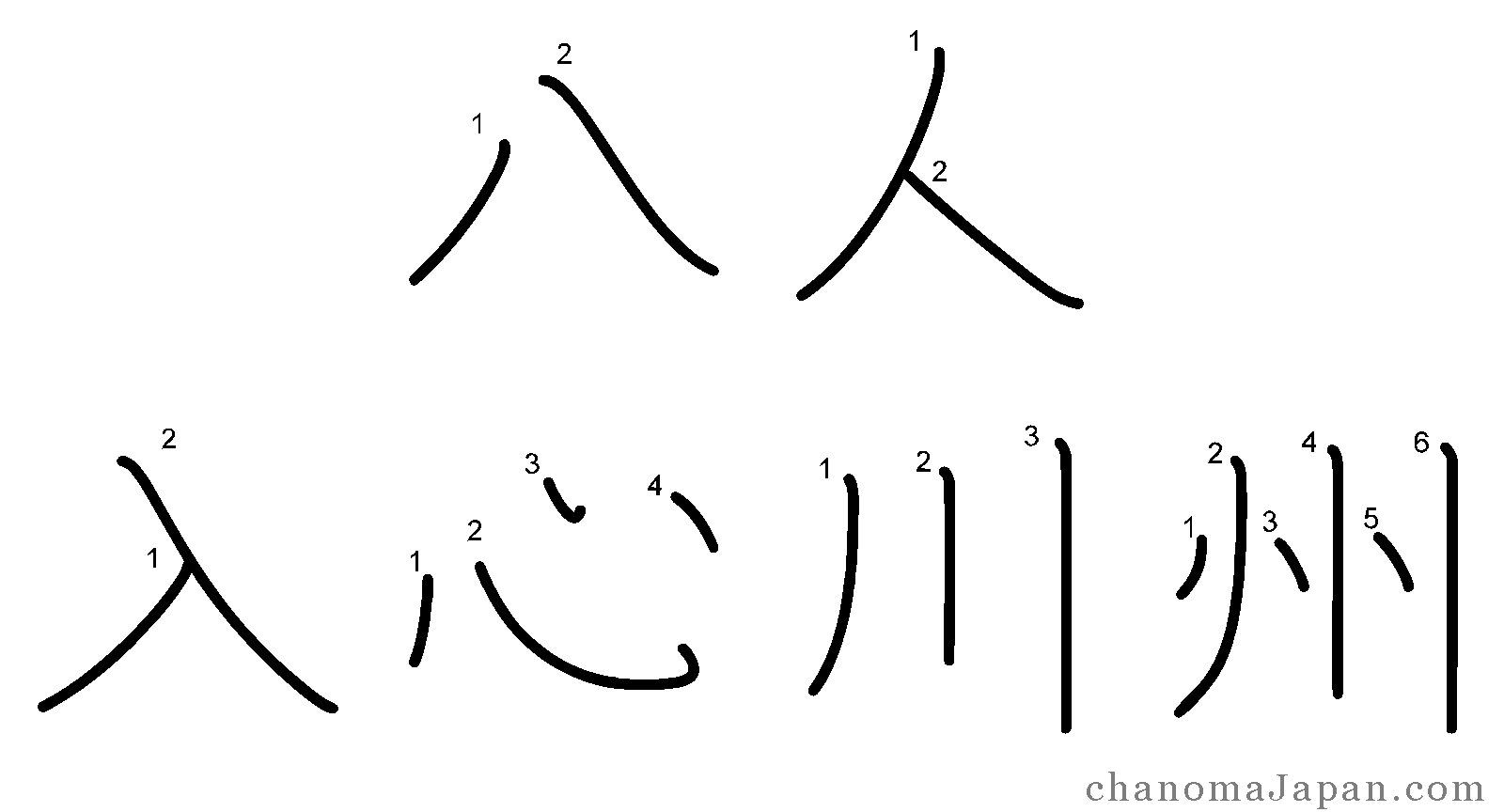

SO rule 1: left to right

When you have two or more strokes in a character, in what order should they be written?

Stroke order rule 1 says that you should write the leftmost stroke first, then work toward the right.

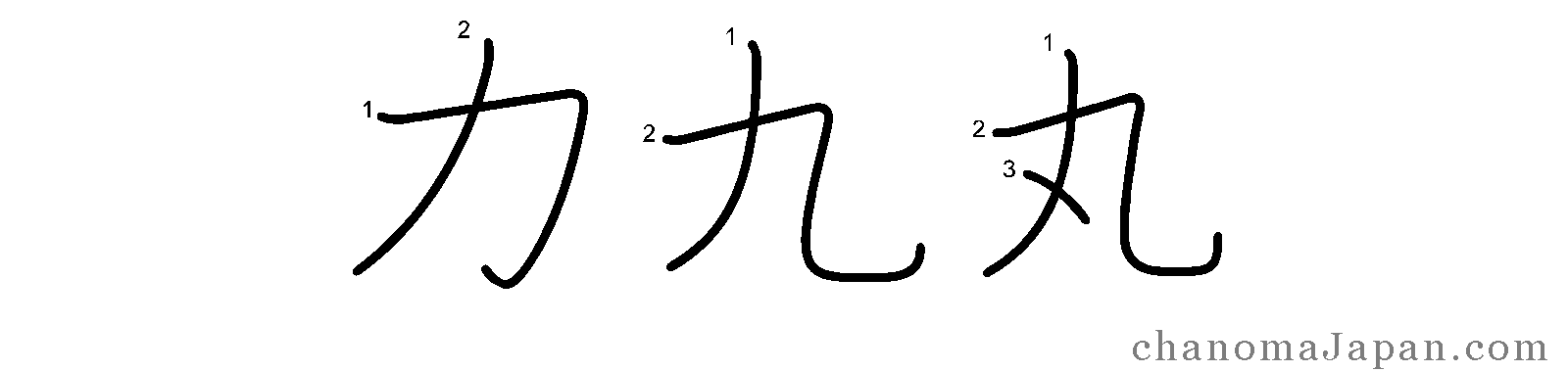

Consider the characters 八 HACHI ‘eight’, 人 hito ‘person’, 入 hairu ‘enter’, 心 kokoro ‘heart’, 川 kawa ‘river’, and 州 SHŪ ‘sandbank’.

Stroke order rule 1 does not apply to characters such as 小 chiisai ‘small’ and 水 mizu ‘water’, which have a central dominant stroke and smaller satellite strokes. We have a separate rule for such characters that we will explore later.

Take 人 hito ‘person’: its two strokes are leaning towards each other; only together can they create a balanced shape. There is no “center of gravity” stroke that gets all the attention, as both strokes in 人 hito are equally important. Similarly, in 川 kawa ‘river’ the three strokes contribute equally to the balance of the character. The same fact is true for the other four characters in the examples above.

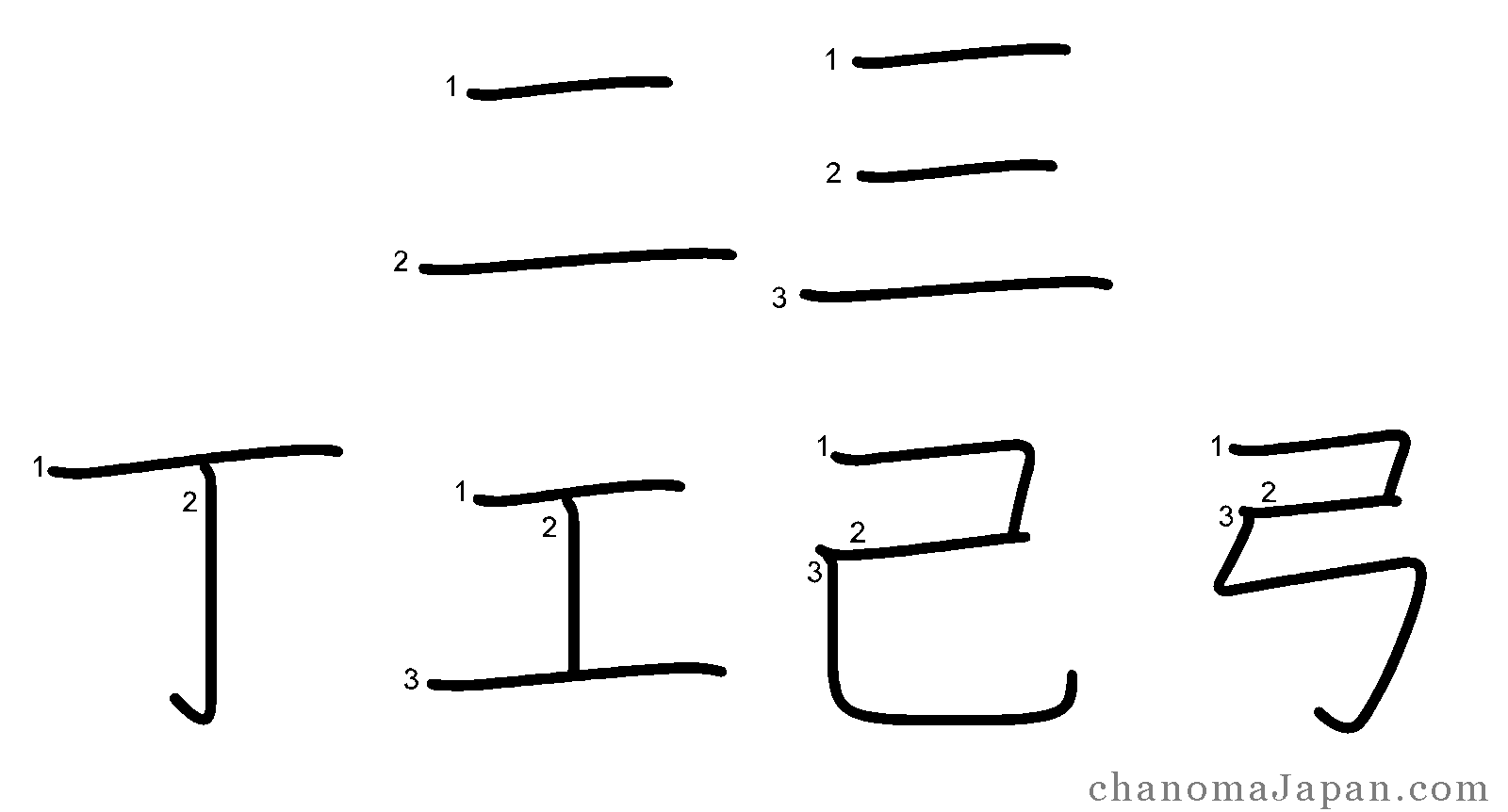

SO rule 2: top to bottom

According to stroke order rule 2, you should write the uppermost stroke written first, then work toward the bottom.

Let’s see 二 NI ‘two’, 三 SAN ‘three’, 丁 TEI ‘T shape’, 工 KŌ ‘craft’, 己 onore ‘self’, 弓 yumi ‘bow’.

二 NI, 三 SAN, 丁 TEI and 工 KŌ are self-explanatory. 己 onore and 弓 yumi may be lightly less obvious.

Take 弓 yumi, for example, and follow the step-by-step instructions below.

- Identify the first stroke, starting from the top (SO rule 2).

- Begin stroke 1 from the left (SD rule 1), make a 90-degree turn toward south, and stop.

- Identify the second stroke, counting from the top (SO rule 2).

- Write stroke 2 from the left (SD rule 1).

- Identify the third stroke, again counting from the top (SO rule 2).

- Write stroke 3 from the top (SD rule 2), making two 90-degree turns and a small hook to complete it.

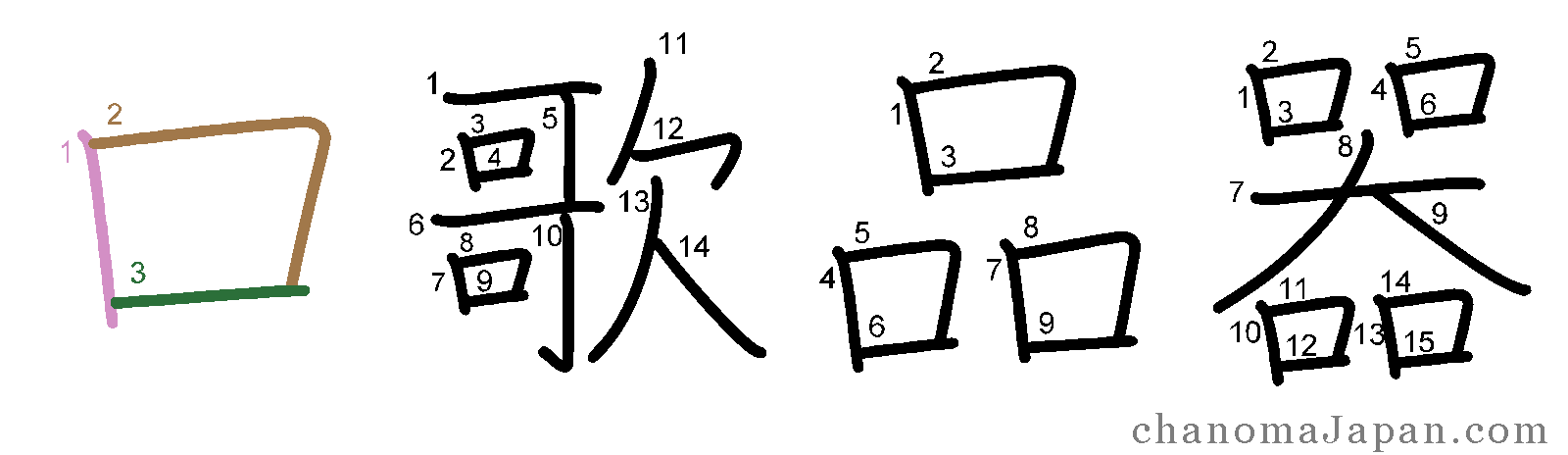

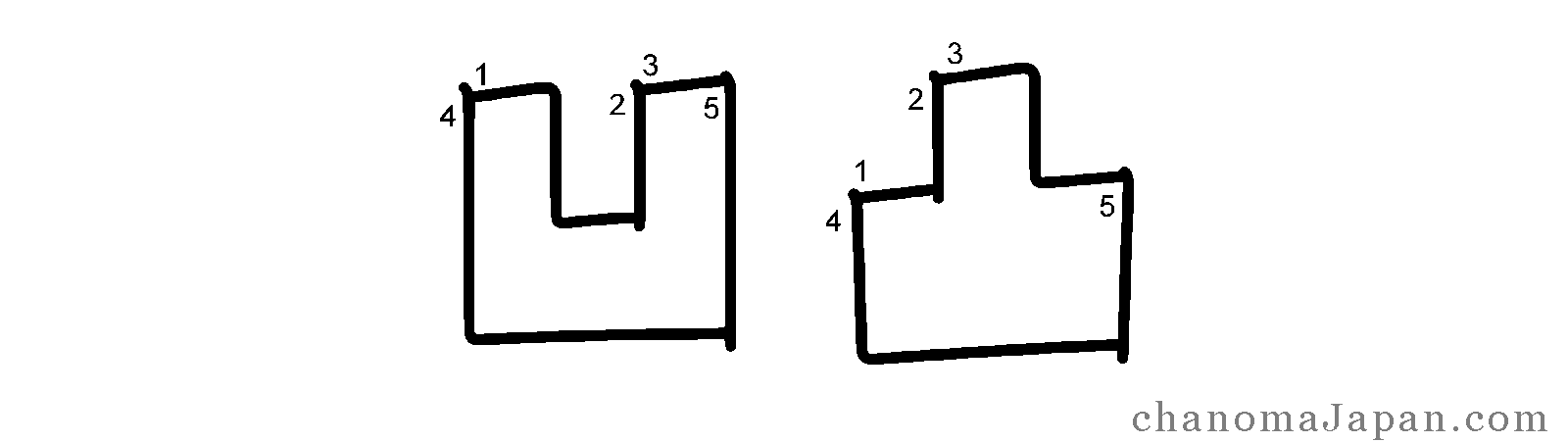

Now that you know stroke direction rules 1 & 2, and stroke order rules 1 & 2, we can learn how to write the shape 口 kuchi ‘mouth’, sometimes called the “box shape” or the “square”.

The vertical stroke is written first, followed by the “bent” stroke. The bottom stroke comes last.

SO rule 3: droplet last

A short solitary stroke situated within a shape, or at the top-right of a shape, is written last. For simplicity, I call such strokes “droplets”.

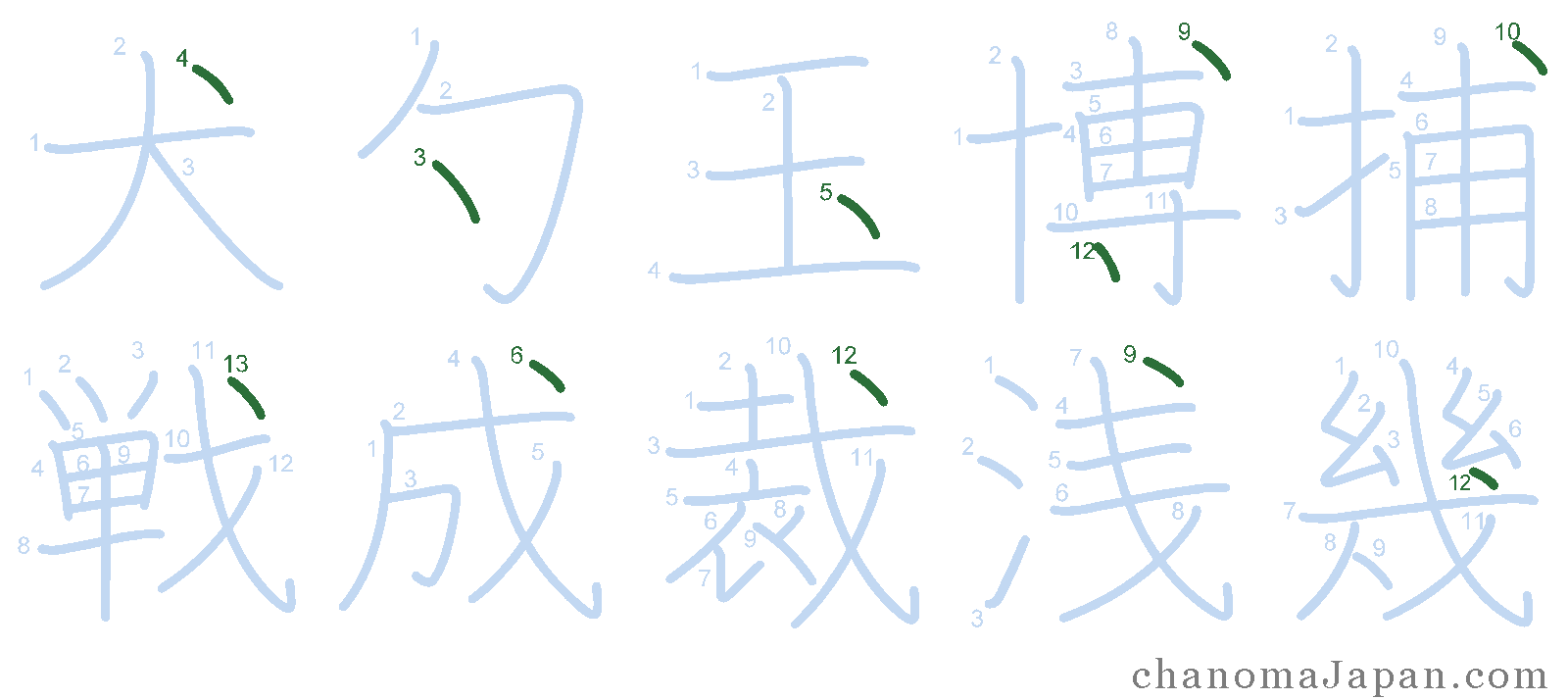

Below: 犬 inu ‘dog’, 勺 SHAKU ‘ladle’, 玉 tama ‘jewel’, 博 HAKU ‘doctor’, 捕 toraeru ‘to capture’, 戦 ikusa ‘war’, 成 naru ‘to become’, 裁 sabaku ‘to judge’, 浅 asai ‘shallow’, 幾 ikutsu ‘how many’.

Pay particular attention to 博 HAKU.

This rule is limited to individual shapes, as you can see in 博 HAKU. In this kanji you have two droplets:

- the firt droplet (stroke 9) is the last stroke of its own shape, the shape above 寸 SUN;

- the second droplet (stroke 12) is the last stroke its own shape, which is 寸 SUN.

I’ll illustrate the same concept with the help of another kanji.

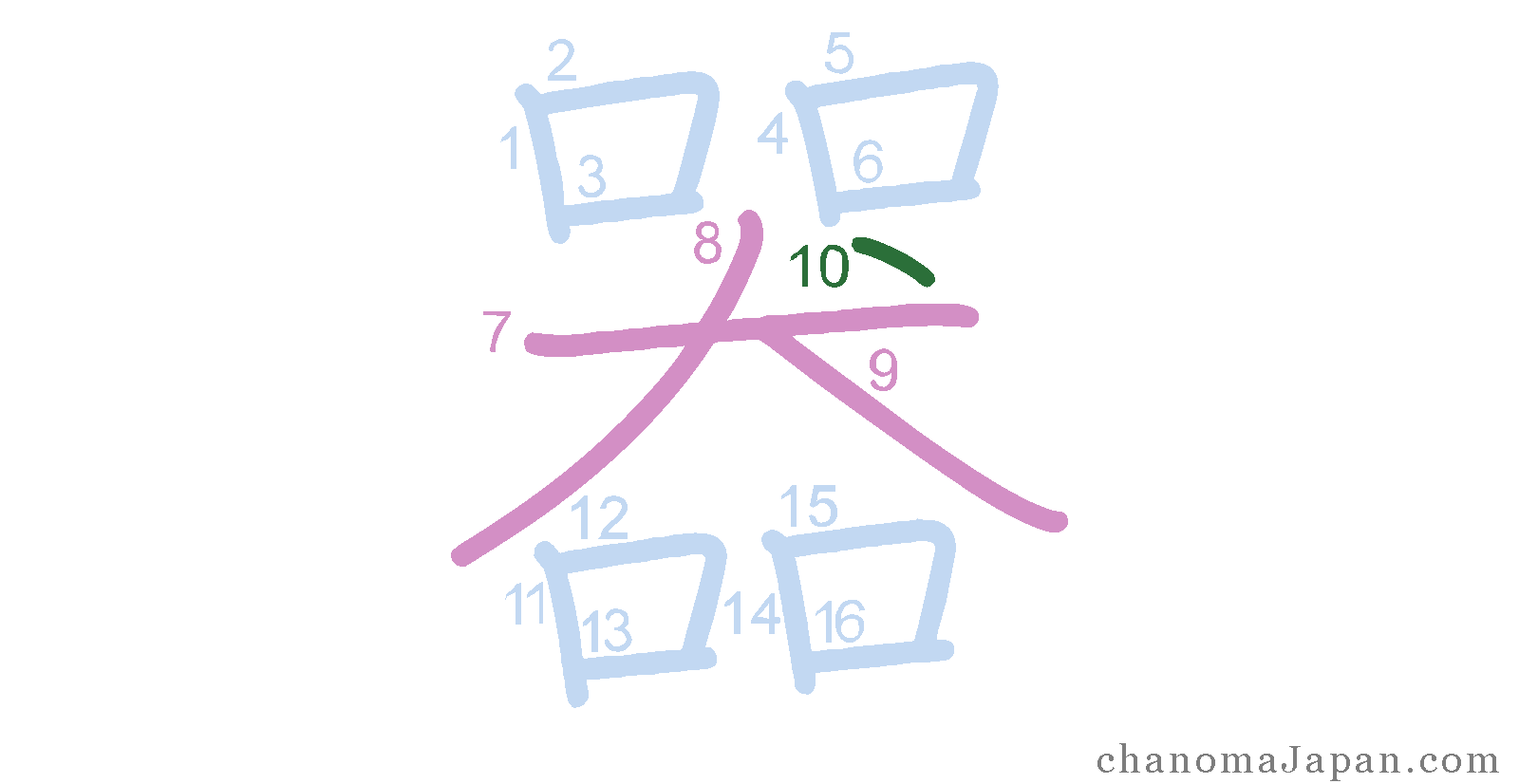

Other kanji are made up of two or more shapes. The kanji 器 utsuwa ‘vessel’ is the result of the union of four 口 SAI ‘vessel’ shapes, and one 犬 inu ‘dog’ shape. That’s a total of five shapes within one kanji.

NB: please notice that ever since the careless kanji simplification enacted by the Japanese government in 1946, this kanji is written without the droplet.

As you can see, the droplet in the shape 犬 inu is not the last stroke of the entire kanji: it is only the last stroke of the shape it belongs to!

Exceptions: droplets not last!

The droplet last rule only applies to droplet-like strokes that are:

- solitary, and either

- located at the top-right of a shape, or

- within a shape.

If a droplet is located anywhere else, or if more than one droplet is present in its immediate vicinity, then it is not written last.

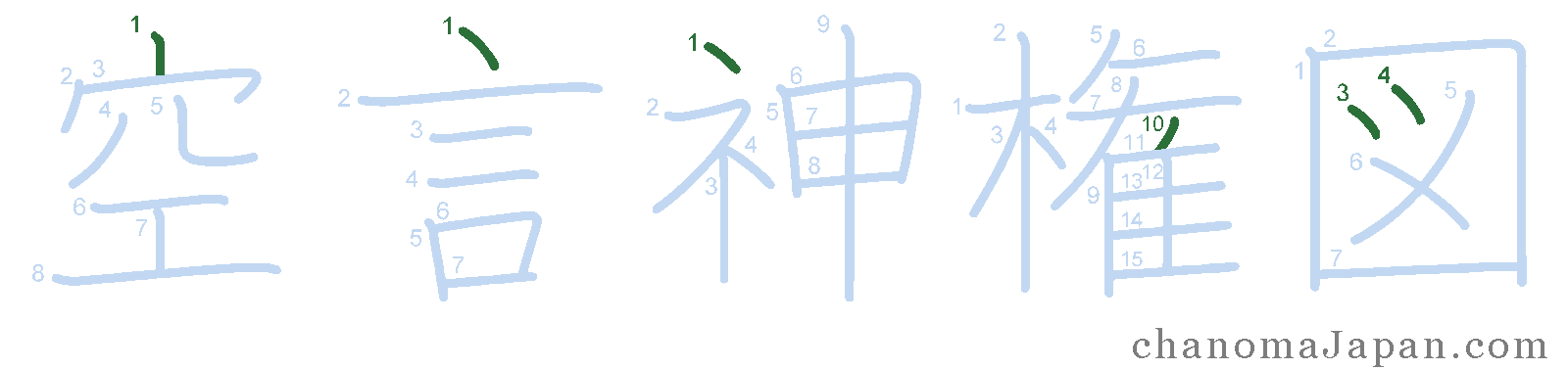

Let’s see 空 sora ‘sky’, 言 iu ‘to say’, 神 kami ‘god’, 権 KEN ‘authority’, 図 ZU ‘diagram’.

- The droplets in 空 sora and 言 iu are solitary; however, they are located in the top-central (rather than top-right) position within their shapes. As such, they are not written last.

- The droplets in the shapes ⺭ shimesu within 神 kami, and 隹 furutori within 権 KEN, are solitary; however, they also are in the top-central position. Therefore they are not written last.

- The droplets in 図 ZU are enclosed within a shape; however, they are not solitary. Because they are not solitary, they are not written last.

All the droplets in these kanji follow normal stroke order rules.

SO rule 4: crossing horizontal first

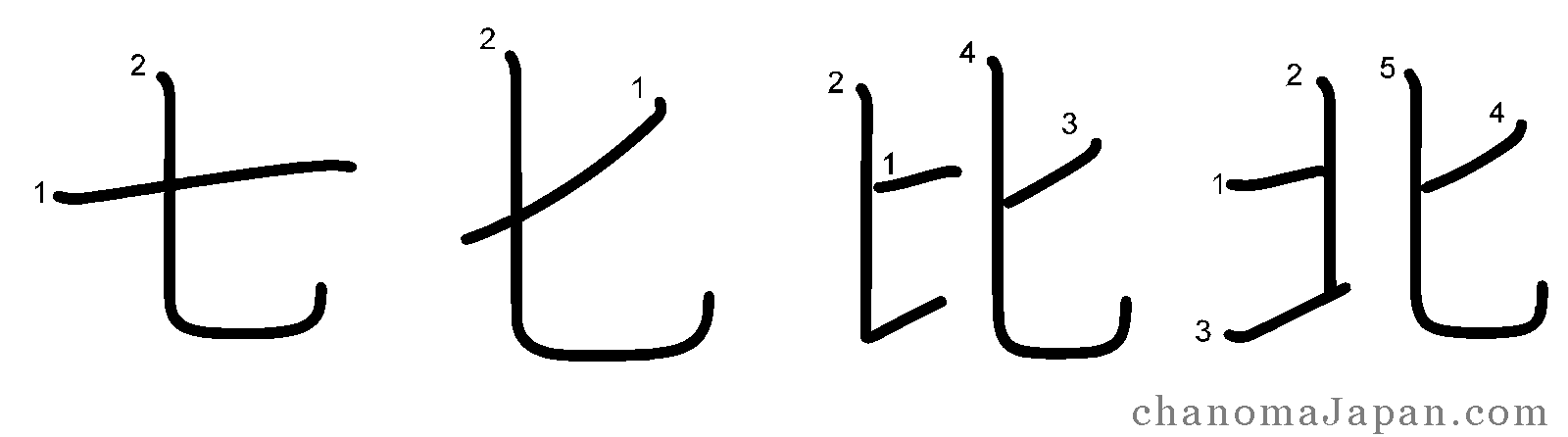

When two strokes intersect, forming a plus shape (+), the horizontal stroke is written first.

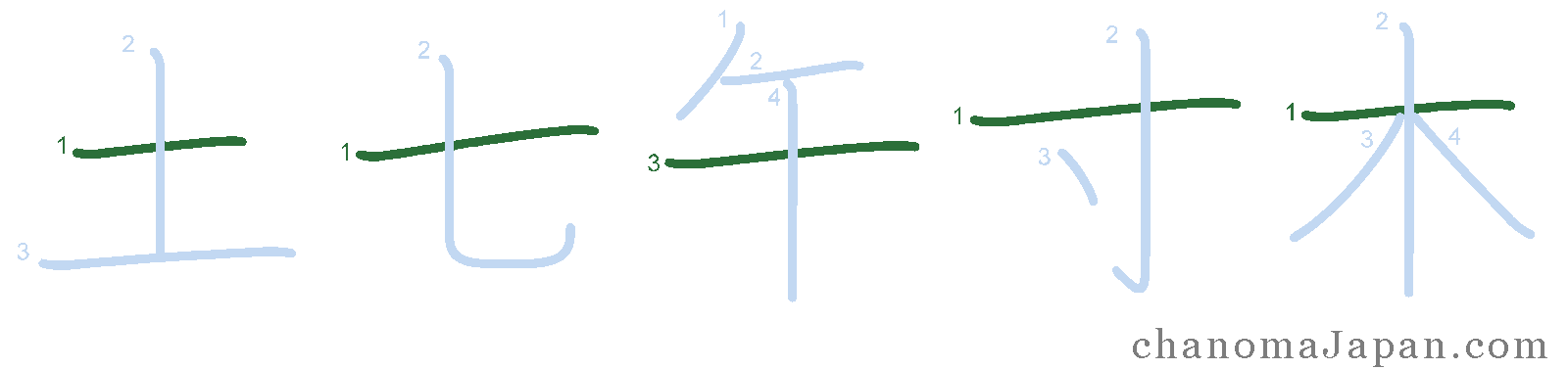

The characters in the image above are: 土 tsuchi ‘earth’, 七 SHICHI ‘seven’, 午 GO ‘noon’, 寸 SUN ‘measurement’, 木 ki ‘tree’. We can see how, when there is a horizontal stroke crossing a vertical stroke, the horizontal stroke is written first.

Exceptions: rice field & king

There are two major exceptions to stroke order rule 4 that should be remembered and practised. They are exceptions because the crossing horizontals do not come first.

We have:

- 田 ta ‘rice field’ shape exceptions, and

- 王 Ō ‘king’ shape exceptions.

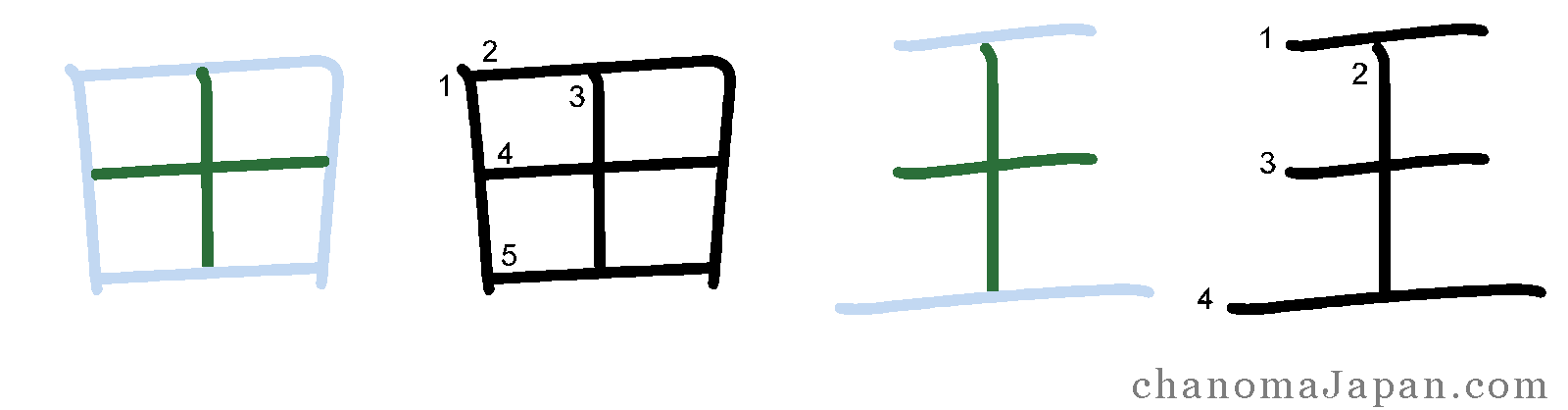

I highlighted the ‘crosses’ that are the subjects of this exception in the diagram below. According to stroke order rule 4, the horizontal stroke in 田 ta and 王 Ō should be written first, but as we can see, they are not.

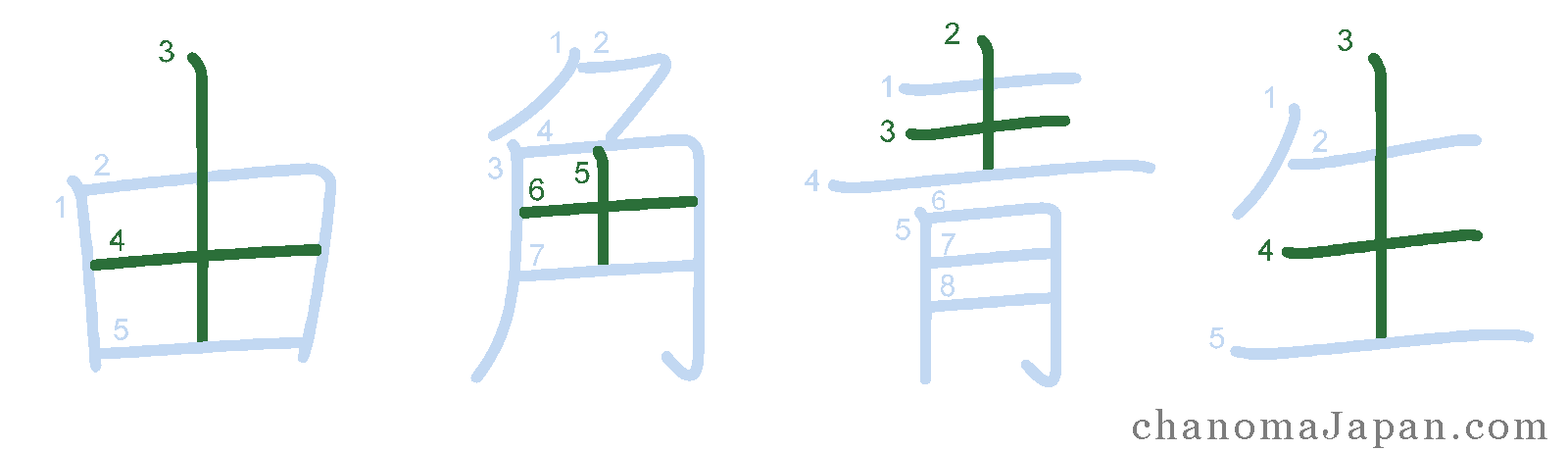

In the image below, the kanji 由 YŪ ‘a reason’ and 角 kado ‘corner’ contain 田 ta type exceptions; the kanji 青 ao ‘blue’ and 生 ikiru ‘to live’ contain 王 Ō type exceptions.

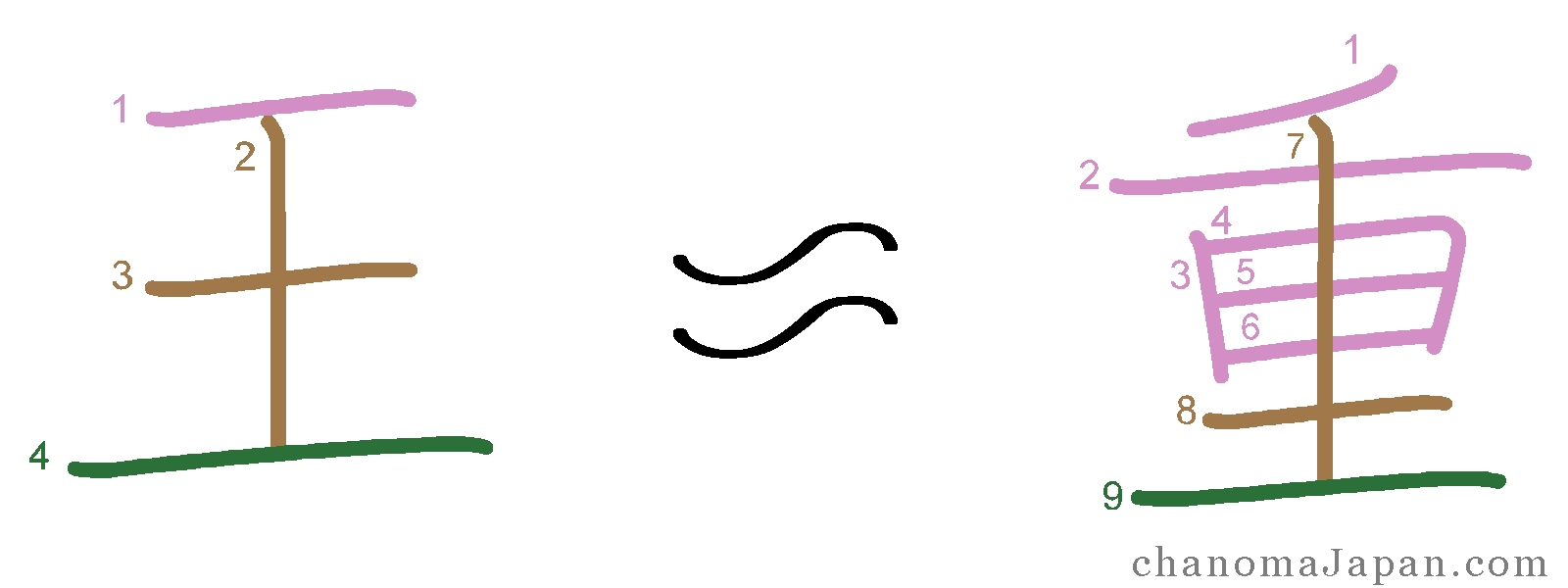

A more subtle 王 Ō type exception is present in the kanji 重 omoi ‘heavy’.

It helps to equate the first six strokes in 重 omoi to the first stroke of 王 Ō: the kanji 重 omoi is carrying a heavier weight, but the principle remains the same.

Practice these exceptions until your hand has memorised them.

Exception: old bird

There is one more notable exception to stroke order rule 4, which could be described like so.

A vertical stroke is written first when it is crossed by two or more horizontal strokes, and is touching but not crossing a lower horizontal stroke.

Let’s call this exception the 隹 furutori ‘old bird’ type exception.

Above, the kanji: 隹 furutori ‘old bird’, 勤 tsutomeru ‘to work for’, 確 tashika ‘sure’, 馬 uma ‘horse’.

If you study the 隹 furutori shape, you’ll see that the vertical stroke (stroke 5) is intersected by two horizontal strokes (strokes 6 and 7), and at the same time is delimited by stroke 8, ie stroke 5 is touching but not protruding beyond stroke 8.

Now let’s study 馬 uma ‘horse’, where exactly the same things is happening. Stroke 3 (the vertical) is cut by strokes 4 and 5 (horizontals), and is stopped by stroke 6.

Under these exact conditions, we write the vertical stroke first, and the horizontal strokes next, in contravention of stroke order rule 4 that says: “crossing horizontal first”.

SO rule 5: prominent middle first

Sometimes strokes within a shape find balance through symmetry. Stroke order rule 5 says that if there is a prominent middle stroke that acts as a centre of mass, that stroke is written first. The satellite strokes, revolving around the centre of mass, are written according to the rules that we have already seen, ie left to right and top to bottom.

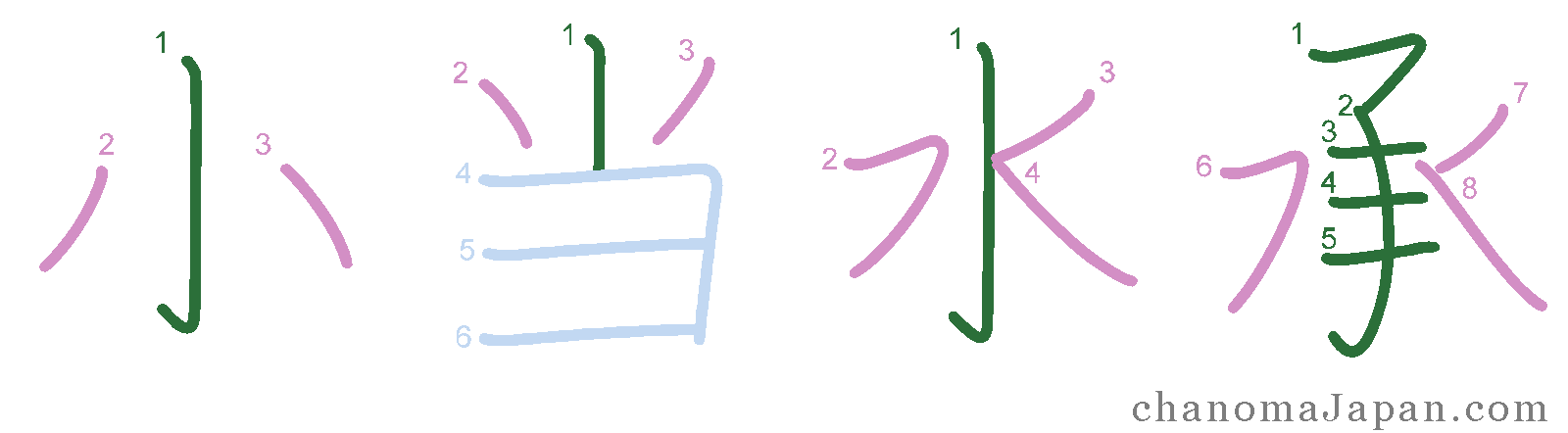

Below we have two 小 chiisai ‘small’ type shapes, and two 水 mizu ‘water’ type shapes. They are very common shapes that you will see in dozens of kanji. Following stroke order rule 5, the prominent middle is written first.

The kanji are: 小 chiisai ‘small’, 当 ataru ‘to hit’, 水 mizu ‘water’, 承 uketamawaru. The centre of mass is shown in green, whereas its satellites are shown in red.

You must have noticed from the diagram above that the prominent middle could be any number of strokes. In 承 uketamawaru ‘to hear’, the prominent middle is made of 5 strokes, and the remaining three satellite-strokes revolve around it.

The observation in the previous paragraph will make more sense once we introduce the concept of components.

Common mistake: three crown droplets

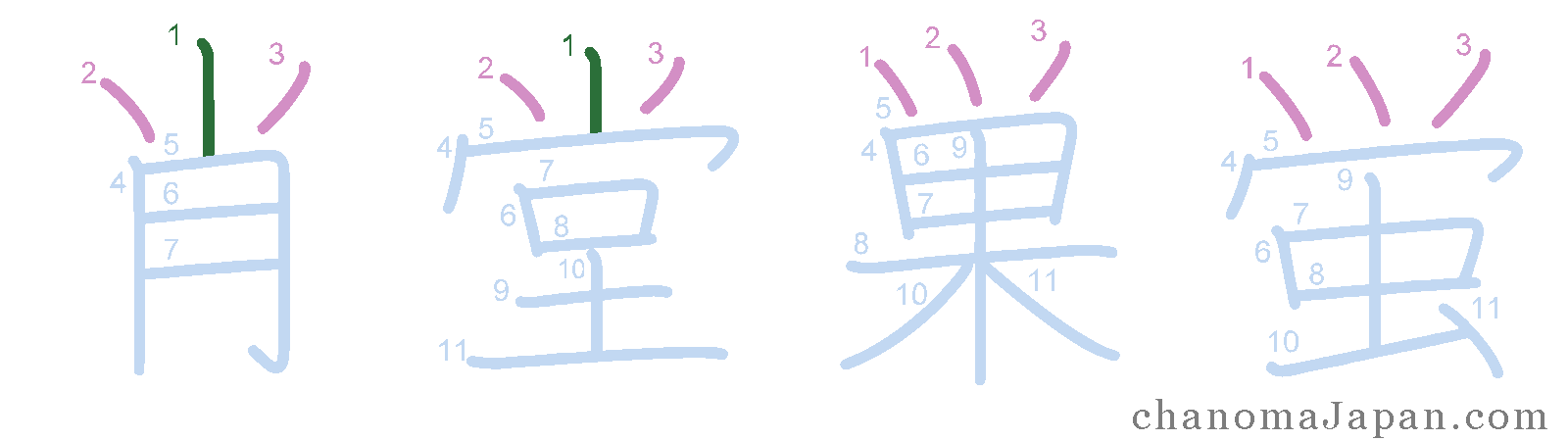

Pay attention to the two crown shapes in the diagram below; these crown shapes are are both made with three droplets. You should be able to see that in the first two characters the three droplets seem to be static, in a quiet balance imposed by a centre of gravity.

By contrast, in the last two characters the droplets are “in motion”, ie they appear to be dynamic.

Obviously, in the characters 肖 SHŌ ‘resemblance’ and 堂 DŌ ‘hall’, the three droplets are governed by the prominent middle first rule. This crown shape closely resembles the kanji 小 chiisai ‘small’.

In the characters 巣 su ‘nest’ and 蛍 hotaru ‘firefly’, the three droplets represent a completely different shape that has no centre of mass. The three strokes simply follow the left to right rule.

This crown shape is practically the same as the katakana ツ tsu, both in shape and stroke order.

More satellite shapes

We should notice two things:

- it is not uncommon for a prominent middle stroke to support multiple satellites;

- the satellite strokes are not always arranged in a perfectly symmetrical way.

The examples seen so far are quite symmetrical (小 chiisai, 当 ataru, 水 mizu, 承 uketamawaru). Let’s see a few more examples where the satellite strokes are more numerous, and less symmetrical.

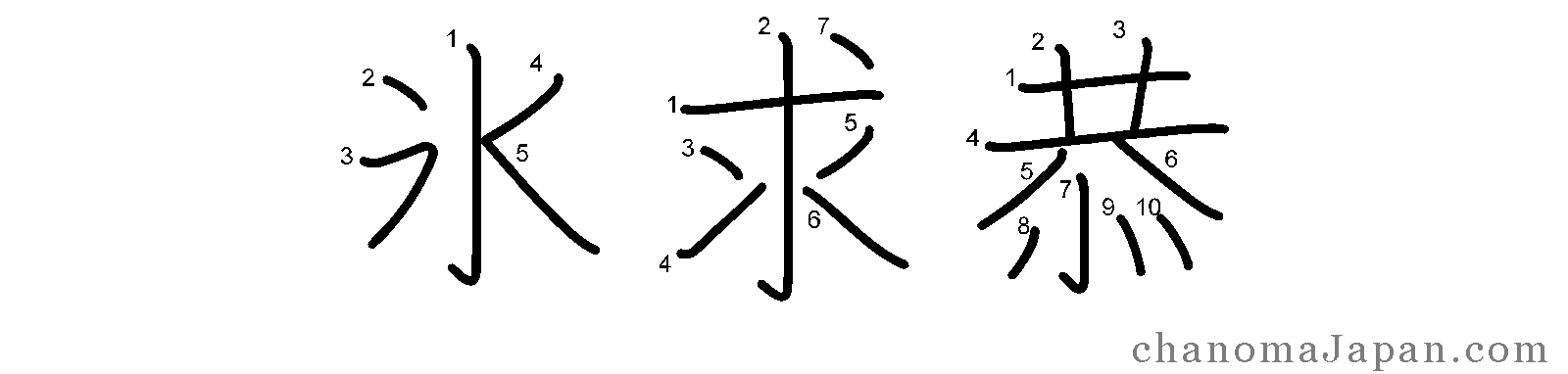

Have a look at the characters 氷 kōri ‘ice’, 求 motomeru ‘to seek’, and 恭 uyauyashii ‘respectful’.

求 motomeru is particularly sweet, as it illustrates in a single kanji both:

- the prominent middle first rule and

- the droplet last rule.

恭 uyauyashii presents a somewhat asymmetrical shape following the prominent first rule. The seventh stroke is the centre of mass, and the remaining short strokes are the satellites, written according to the left to right rule.

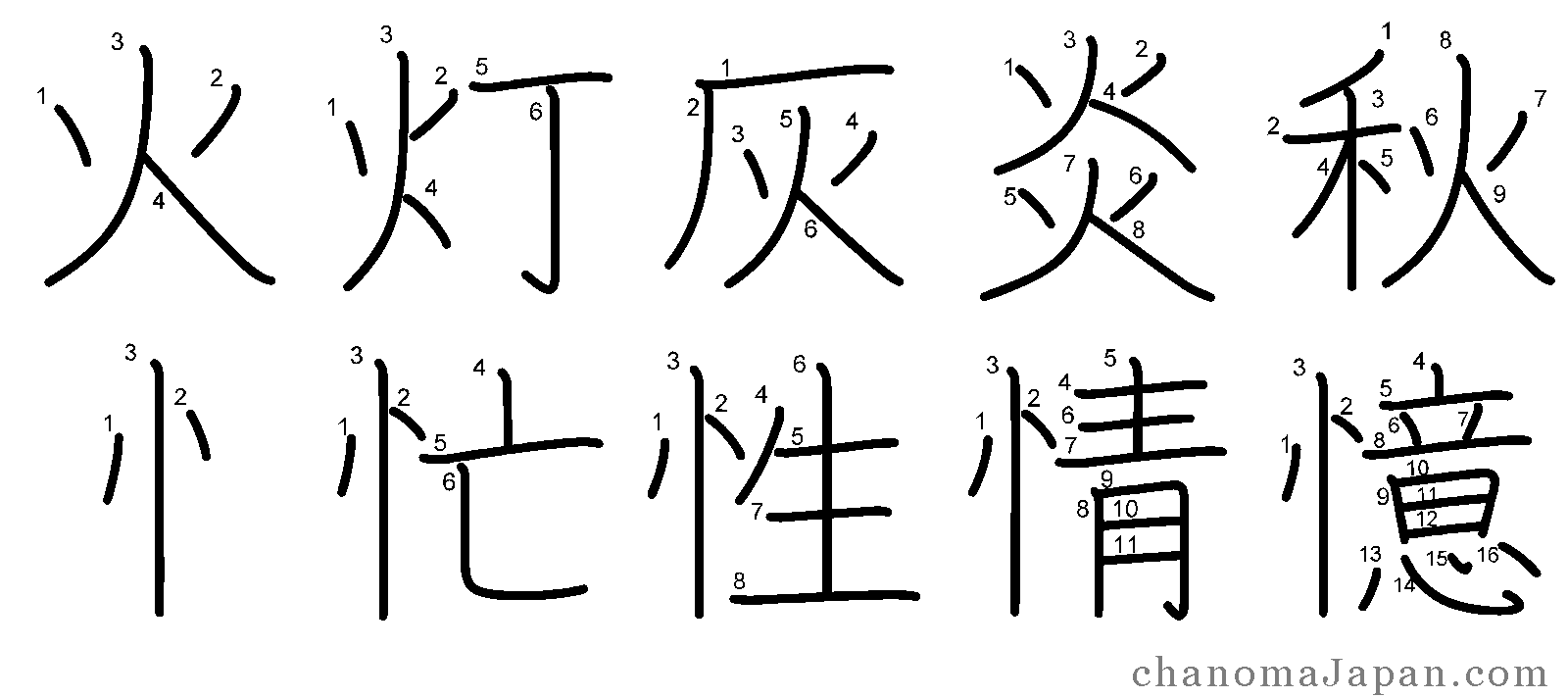

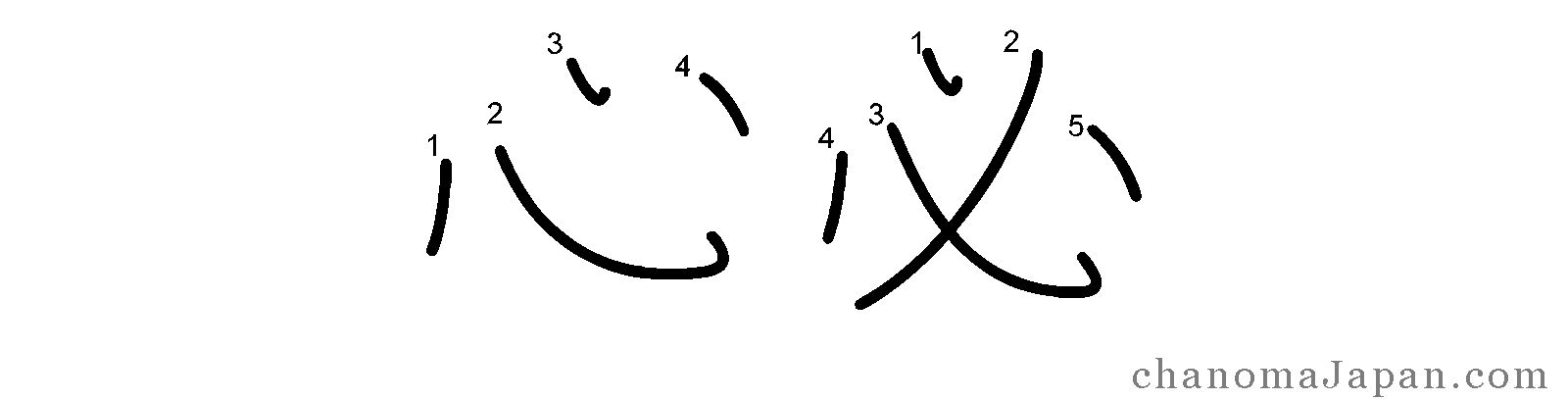

Exceptions: heart & fire

Two bold exceptions are 火 hi ‘fire’, and the 忄 risshinben ‘heart’ shape, which should be written as shown here.

Notice how in 火 hi the prominent middle is the combination of strokes 3 and 4.

In these two shapes, 火 hi and 忄 risshinben, the rule is practically inverted, since you have to write the prominent middle stroke(s) last. They are very important exceptions because they are common components in a great number of kanji.

Write these shapes a hundred times each until the correct stroke order becomes a reflex in your hand.

SO rule 6: horizontal skewer last

A horizontal stroke that pierces a whole shape and protrudes from both sides is written last. Let’s call such a stroke “skewer”.

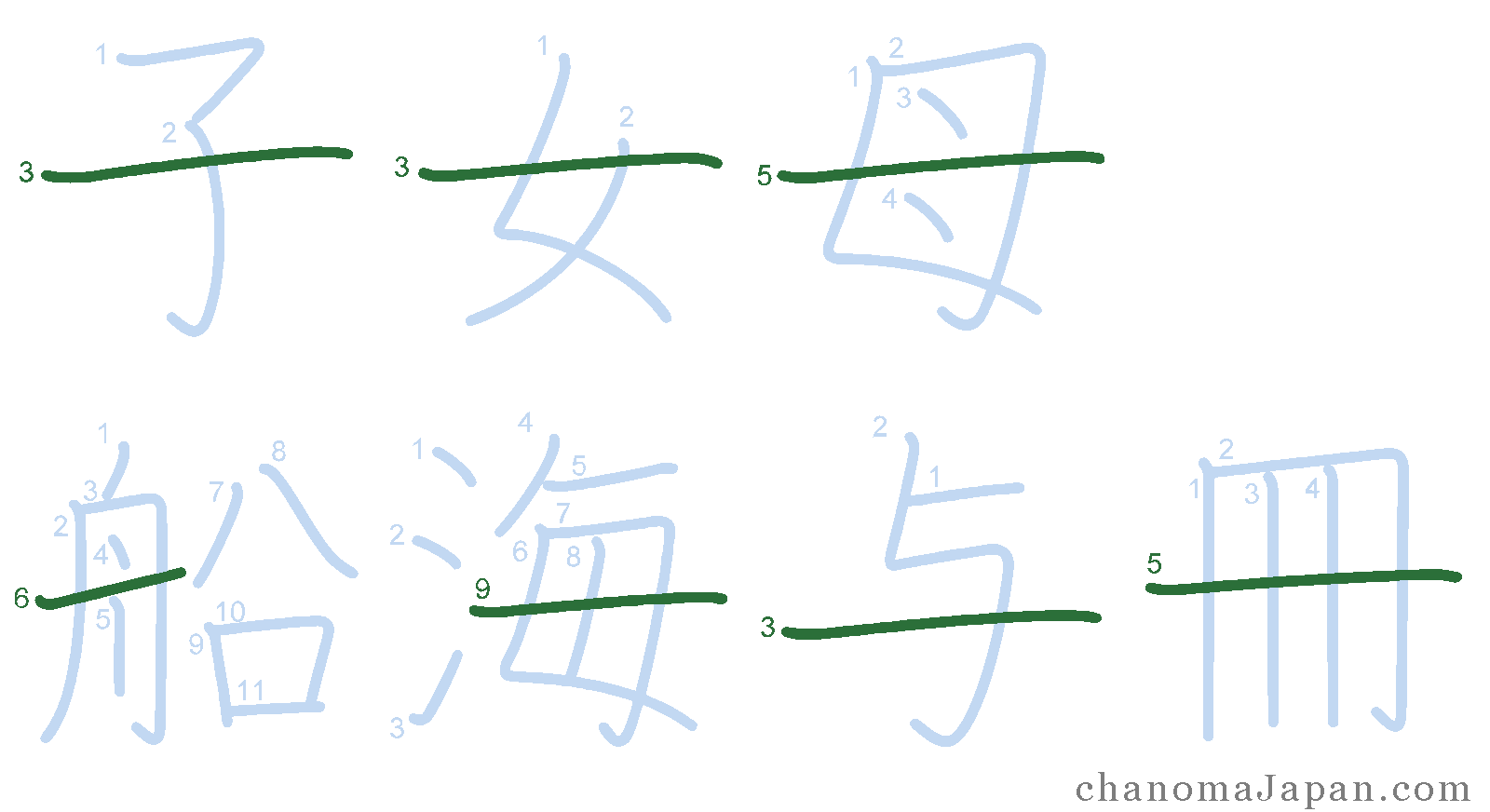

The next diagram contains a very good selection of common kanji containing a horizontal skewer stroke. Let’s learn how to write: 子 ko ‘child’, 女 onna ‘woman’, 母 haha ‘mother’, 舟 fune ‘boat’, 海 umi ‘sea’, 与 ataeru ‘to give’, 冊 SATSU ‘volume’ (as in “book”).

Before we move on to the exceptions, allow me to open a small parenthesis.

This diagram should help clear things up.

In the picture above you can see such an example. Notice how the fifth 与 ataeru (on the right) doesn’t seemingly have a piercing horizontal stroke anymore. The stroke order, obviously doesn’t change.

Clearly, the choice of kanji style is important when studying stroke order, as certain styles can convey the logic behind the stroke order rules much better than other styles.

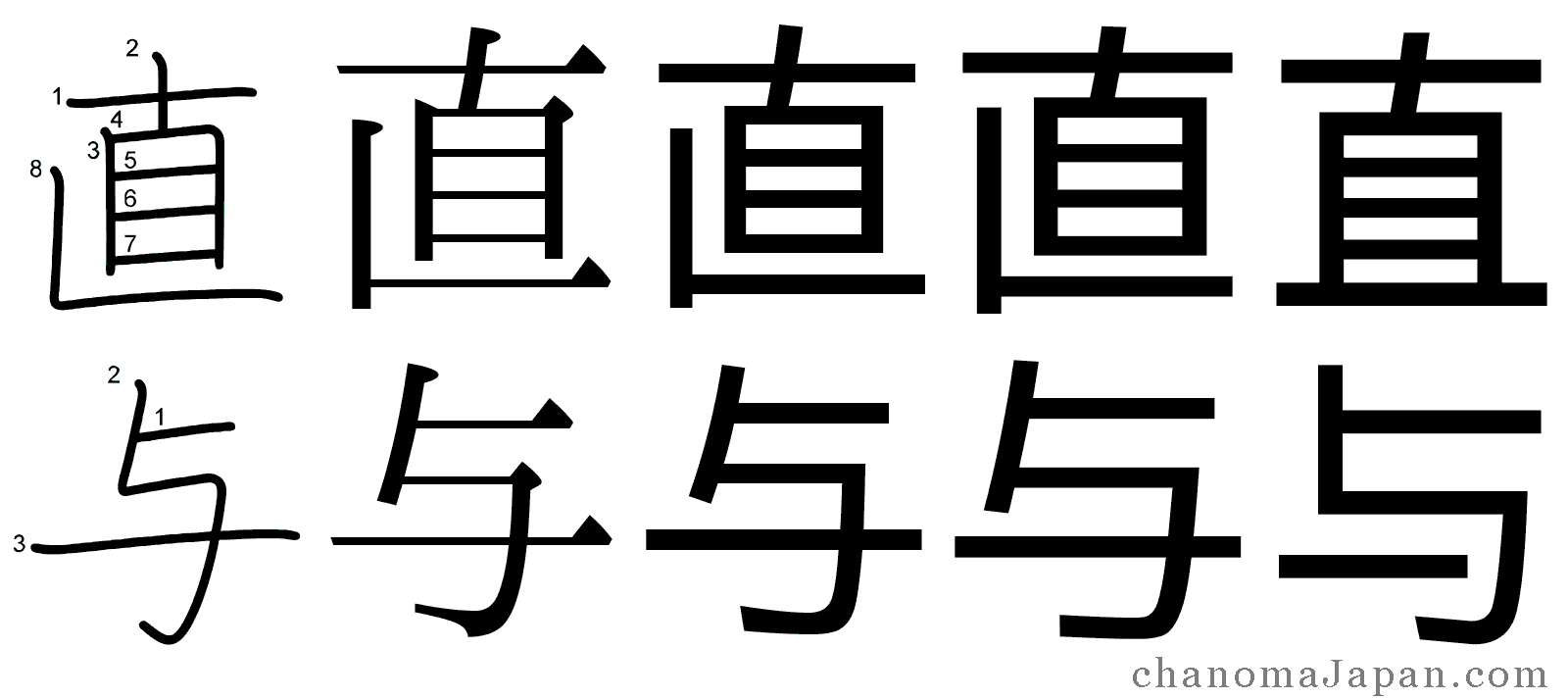

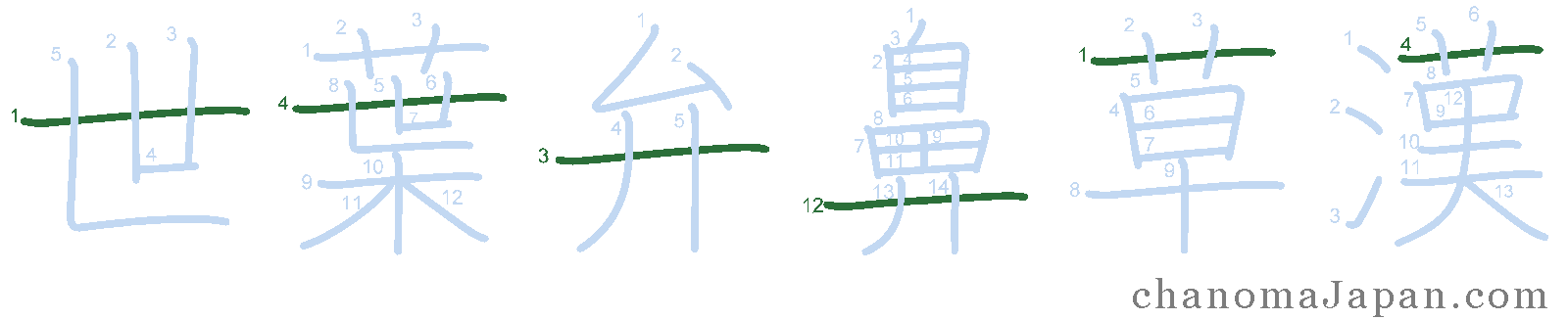

Exceptions: skewers that come first

Three major exceptions are:

- the 世 yo ‘world’ shape,

- the lower shape in 弁 BEN ‘speech’

- and the crown shape in 草 kusa ‘grass’, called 艹 kusakanmuri.

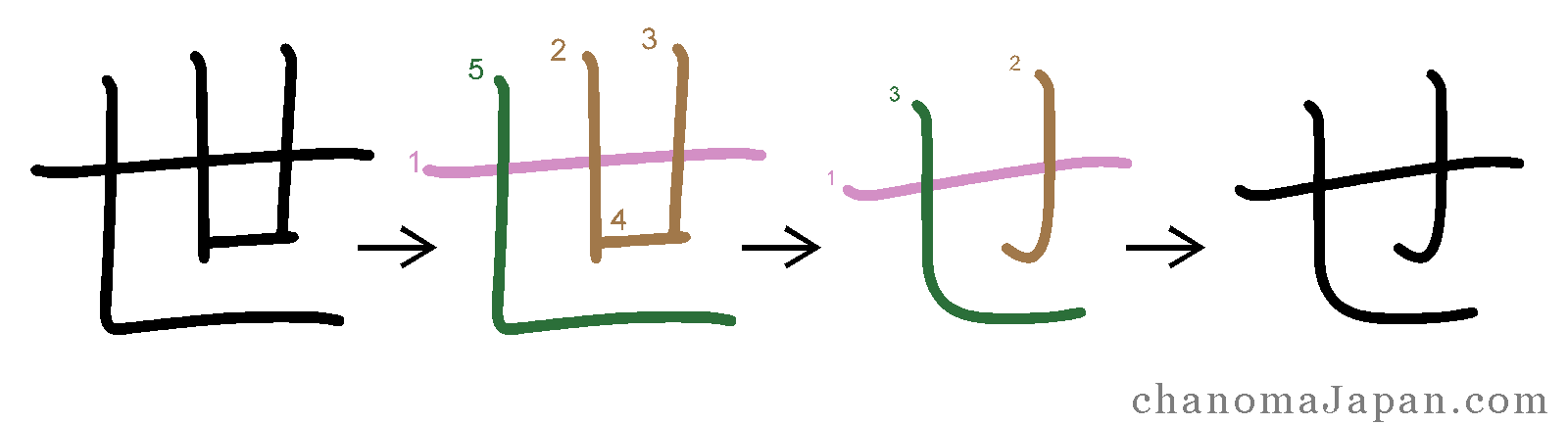

Does the kanji 世 yo remind you of the hiragana せ se? It’s not a coincidence.

世 yo has the on-readings SEI and SE, and it’s where the hiragana せ se comes from. せ se is merely a cursive form of the kanji 世 SE. This is clearly reflected in the stroke order.

If you have already learned the hiragana syllabary, memorising the apparently arbitrary exception 世 SE should be a piece of cake.

We can move on to the next group of exceptions.

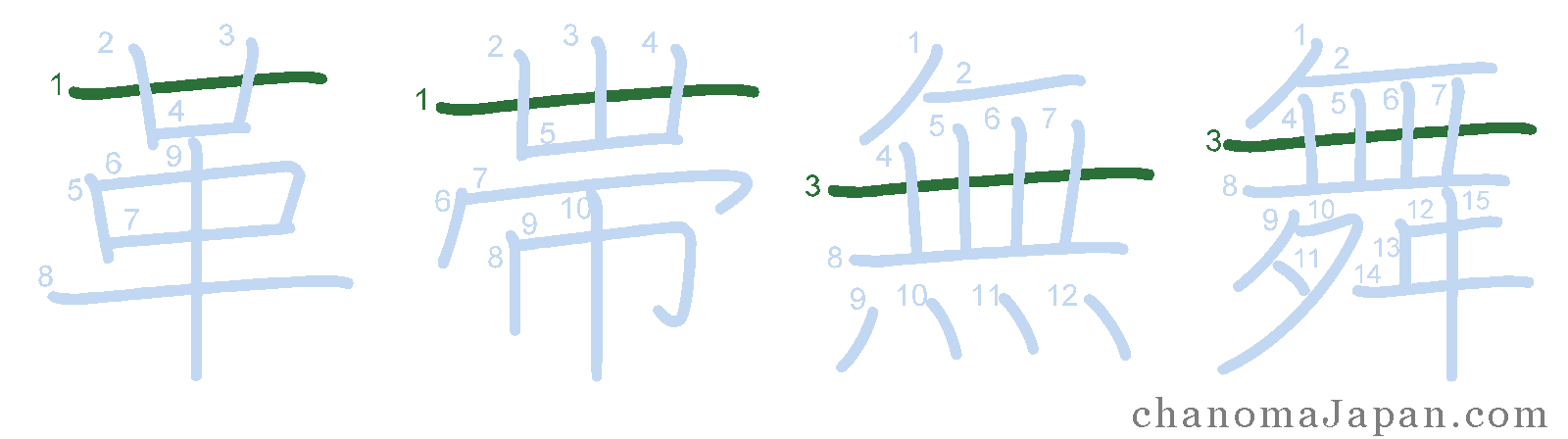

Below we have the kanji 革 kawa ‘leather’, 帯 obi ‘belt’, 無 MU ‘nothing’ and 舞 mau ‘to dance’.

The most interesting kanji is 無 MU, which is also the shape contained in 舞 mau.

無 MU is an extremely common kanji, so it is worth investing a few minutes into memorising its stroke order.

SO rule 7: vertical skewer last

A vertical stroke that pierces a whole shape is written last. Unlike rule 6, the stroke doesn’t have to protrude from both sides. We have two possible configurations illustrated in the diagram below:

- the stroke protrudes from the top and the bottom (top row);

- the stroke protrudes only from the bottom (bottom row).

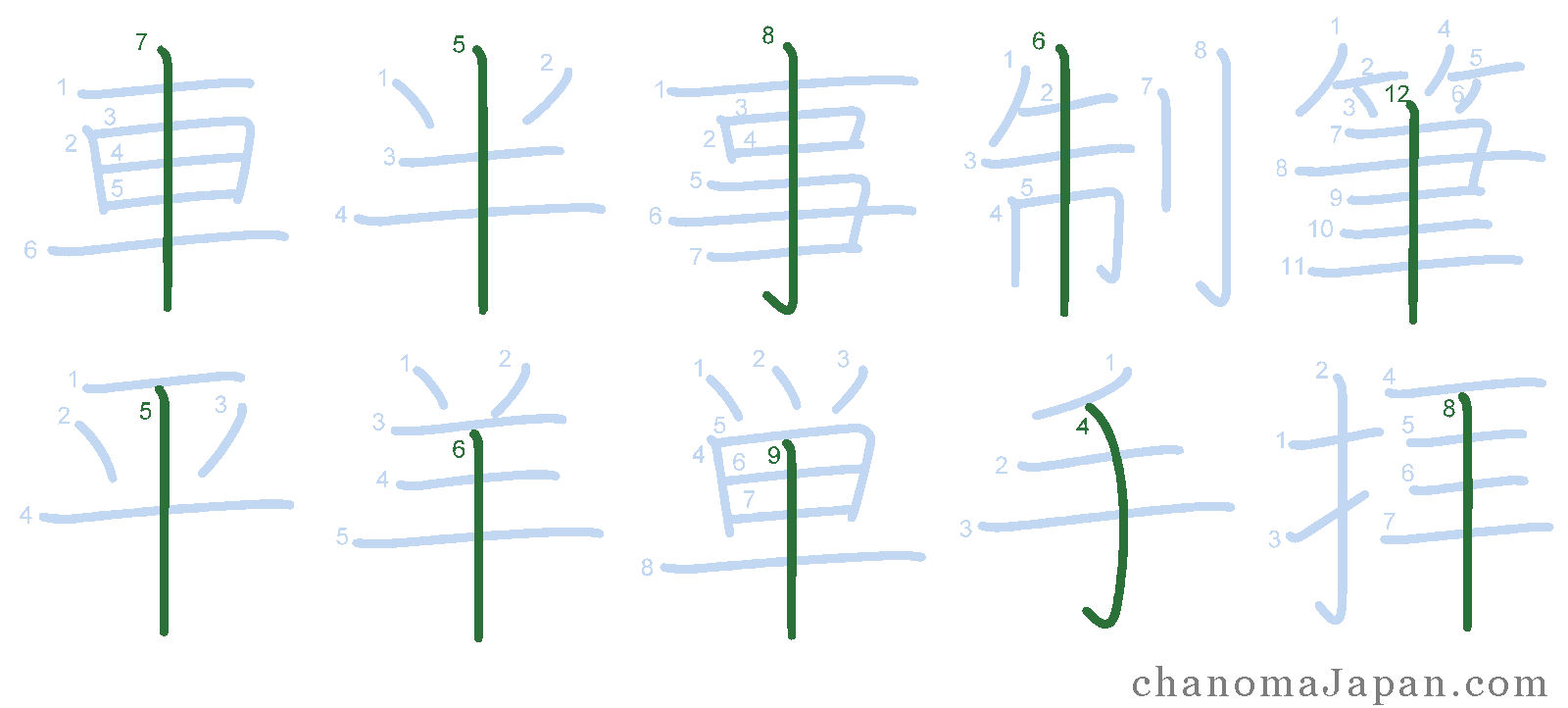

Above we have the kanji 車 kuruma ‘wheel’, 半 nakaba ‘middle’, 事 koto ‘thing’, 制 SEI ‘system’, 筆 fude ‘brush’ (to write), 平 taira ‘flat’, 羊 hitsuji ‘sheep’, 単 TAN ‘simple’, 手 te ‘hand’, 拝 ogamu ‘to pray’.

This rule applies only to the crossing/intersecting part of the shape.

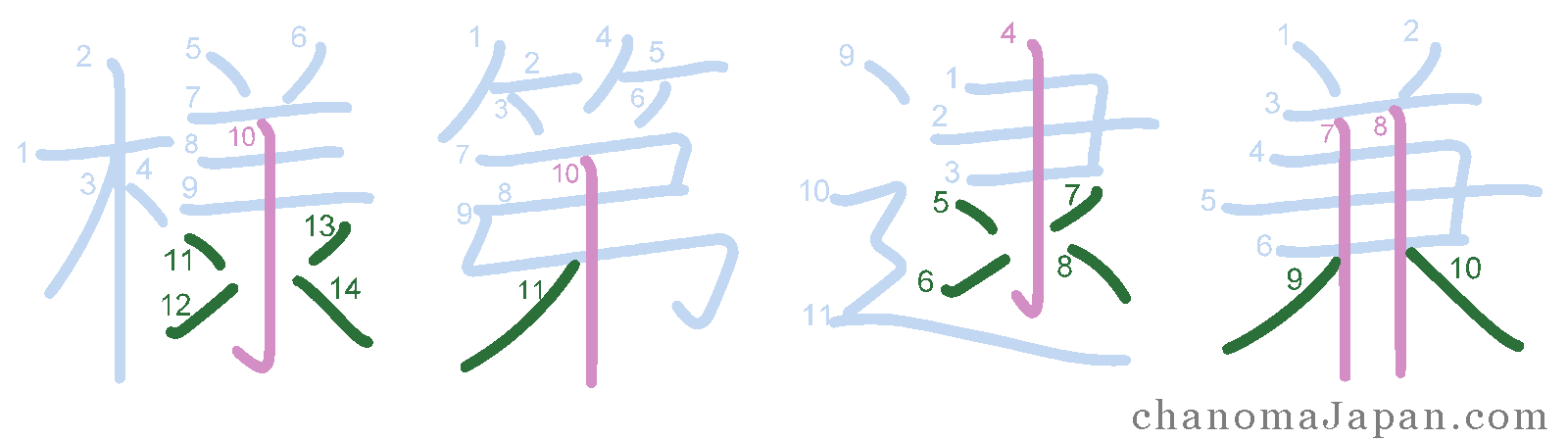

Better see what I mean with the help of some kanji: 様 sama ‘condition’, 第 DAI ‘sequence’, 逮 TAI ‘apprehend’, 兼 kaneru ‘serve both as’.

In the diagram, the vertical stroke is written after all the strokes that are crossed by it, according to the rule, but before all surrounding strokes that are not crossed by it.

There are a few special cases where a vertical skewer that is written last protrudes from the top but not the bottom.

We can consider the shapes contained in the kanji 専 moppara ‘solely’, 唐 TŌ ‘Tang’ (dynasty) and 書 kaku ‘to write’.

These shapes are similar to a kanji such as 土 tsuchi ‘earth’, because a piercing vertical stroke protrudes at the top, but not at the bottom. Unlike 土 tsuchi, though, the vertical skewer in the shapes above is written last.

Non-protruding skewers

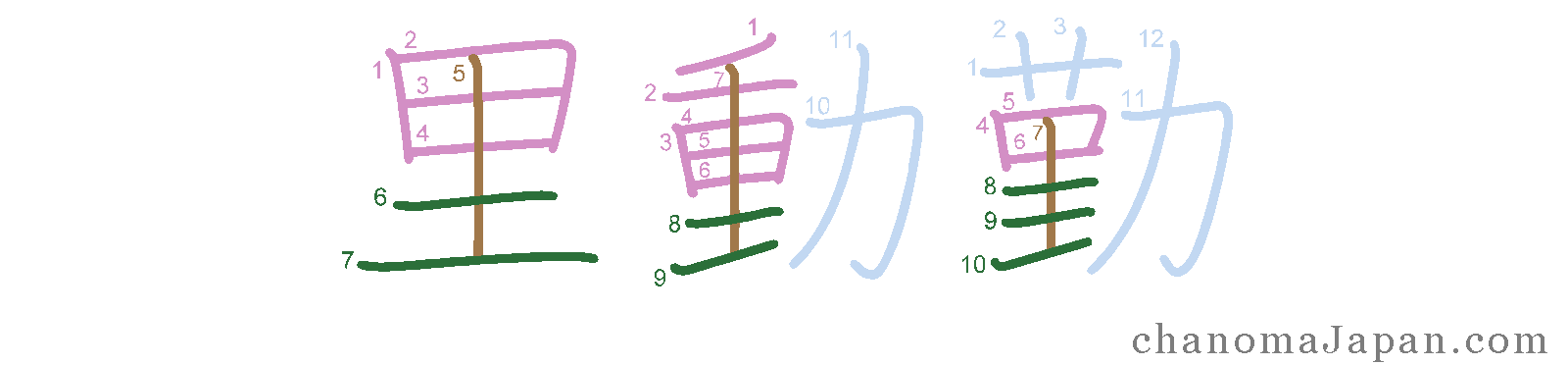

If the piercing vertical stroke is entirely contained between the top and the bottom stroke, then the shape is written in this order:

- upper part (red);

- vertical piercing stroke (brown);

- lower part (green).

The stroke orders of the kanji 里 sato ‘village’, 動 ugoku ‘to move’ and 勤 tsutomeru ‘to serve’ follow this principle.

SO rule 8: hidariharai first

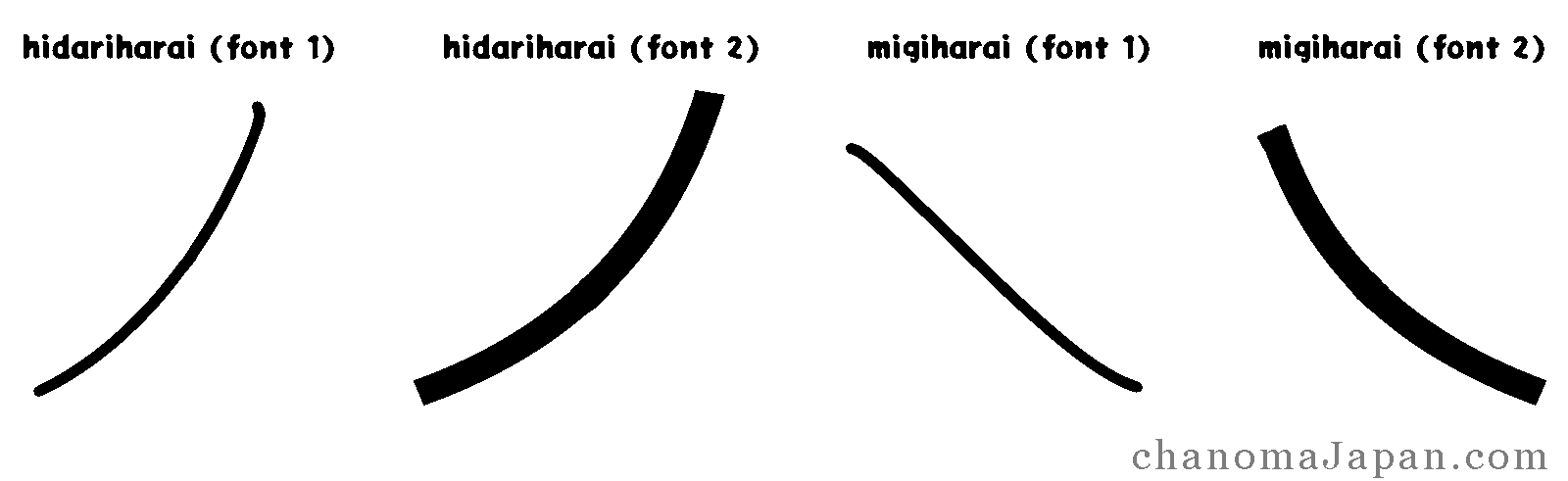

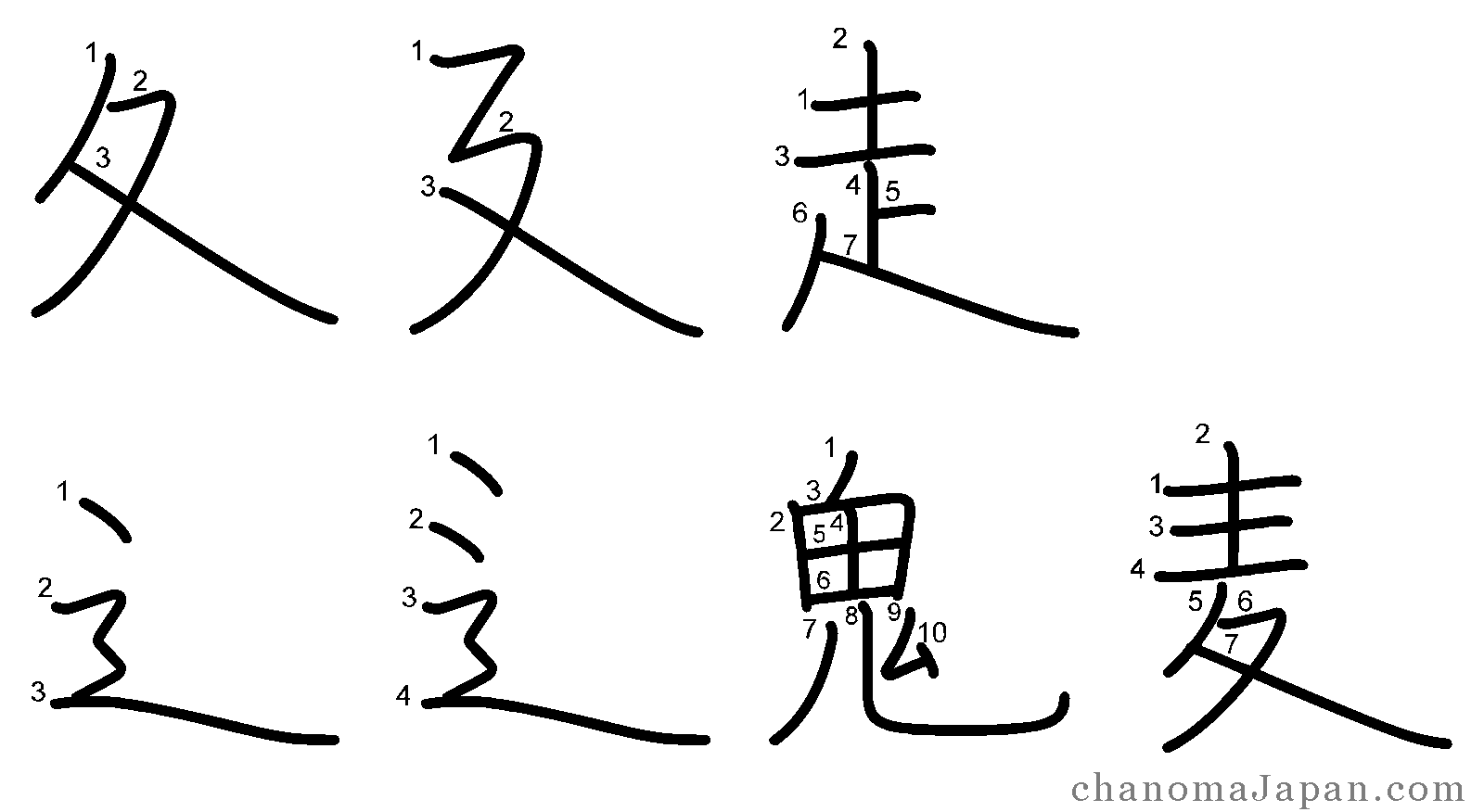

A 左払い hidariharai (lit. “sweeping left”) is a slanted, upper-right-to-lower-left stroke; a 右払い migiharai (lit. ‘sweeping right’) is its mirror image: a slanted, upper-left-to-lower-right stroke. This is what they look like in a serif and a sans-serif font.

Stroke order rule 8 says:

Whenever a hidariharai intersects a migiharai, forming an X-shape, the hidariharai is written first.

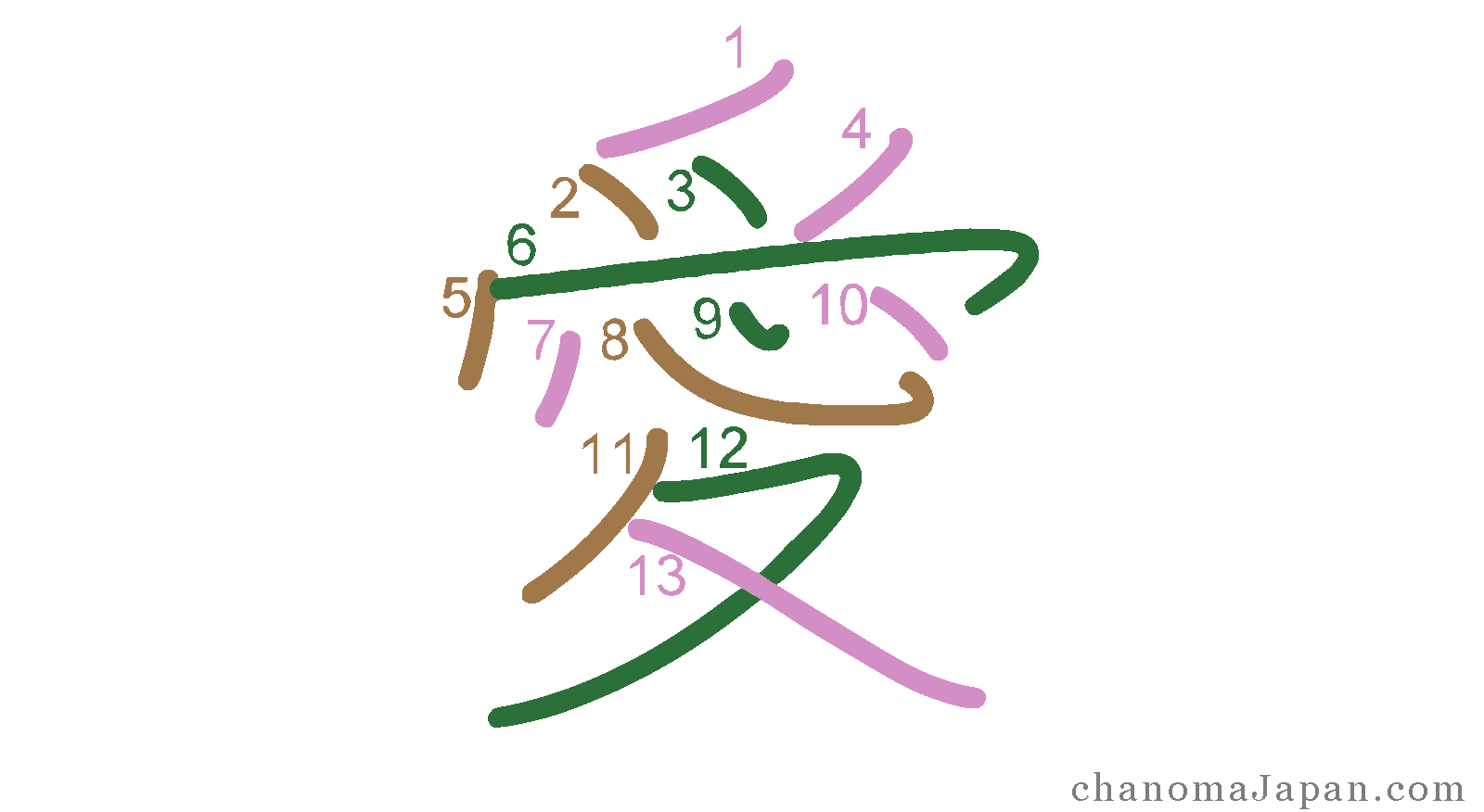

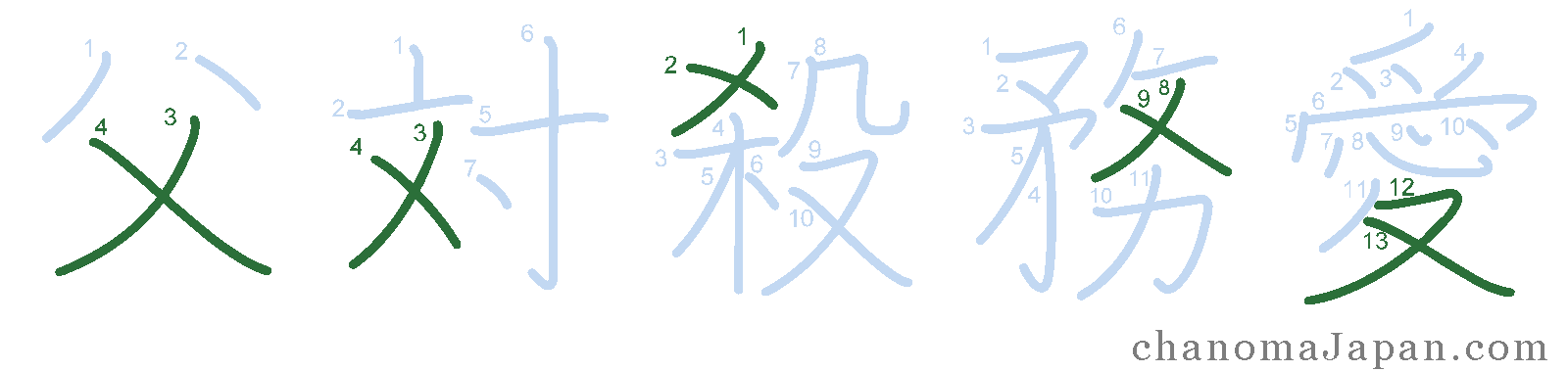

The kanji in the diagram above are 父 chichi ‘father’, 対 TAI ‘against’, 殺 korosu ‘to kill’, 務 tsutomeru ‘to serve’, 愛 AI ‘love’.

The hidariharai in 愛 AI is slightly more elaborated than the basic shape we presented in the previous diagram, but it is treated the same.

There are no exceptions to this rule: you can’t go wrong.

SO rule 9: horizontal vs hidariharai, short first

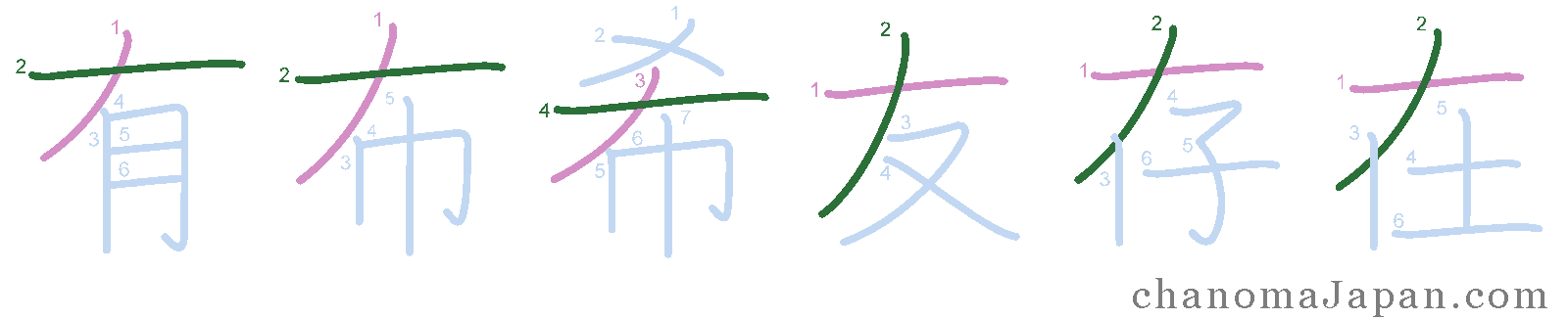

This rule applies to a few but very common characters. Whenever a horizontal stroke and a 左払い hidariharai (described in the previous rule) form a cross, the shorter stroke is written first.

The kanji in the diagram are: 有 aru ‘exist’, 布 nuno ‘cloth’, 希 KI ‘hope’, 友 tomo ‘friend’, 存 SON ‘exist’, 在 aru ‘exist’. (A lot of “exists”!)

Depending on the font used, discerning which stroke is long and which short may become completely arbitrary, which is why I want to include a rule of thumb:

Is this “short first” rule nonsense then? Not really!

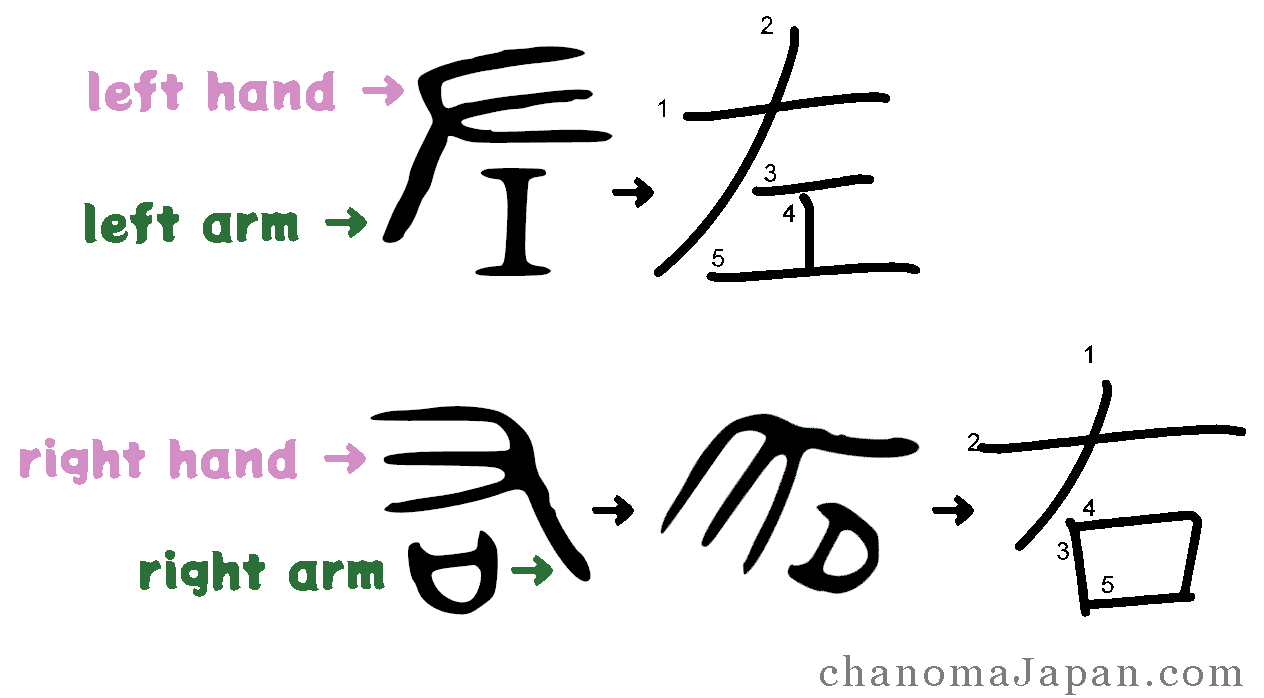

This rule is particolarly handy in memorising the stroke order of 左 hidari ‘left’ and 右 migi ‘right’. The reason that we are talking about longer and shorter strokes is because one stroke represents an “arm”, and the other stroke a “hand”.

The diagram compares the shapes found in the Chinese bronze inscriptions for the characters 左 hidari ‘left’ and 右 migi ‘right’ with the shapes used today. The ancient pictograms show stylised hands and ritualistic objects.

SO rule 10: long crack first

A very long time ago 漢字 kanji, or Chinese characters, used to be inscribed on turtle shells and animal bones for the purpose of divination. The inscribed bone was put on a fire, causing it to crack, allowing the shaman to interpret the signs and predict the future.

The script used in these rituals, called 甲骨文 kōkotsubun, evolved in style throughout the millennia to become the modern kanji.

Surprisingly most kanji preserve, in their modern shapes, the very original shapes and ritualistic meanings.

The shape 卜 uranai ‘divination’ represents a crack on an oracle bone. Stroke order rule 10 says that whenever you see this shape, the “long crack” should be written first.

In the diagram below: 卜 uranai ‘divination’, 占 uranau ‘to divine’, 上 ue ‘up’, 正 tadashii ‘correct’, 足 ashi ‘leg’, 走 hashiru ‘to run’.

In the highlighted 卜 uranai shape, the long vertical stroke is always written first.

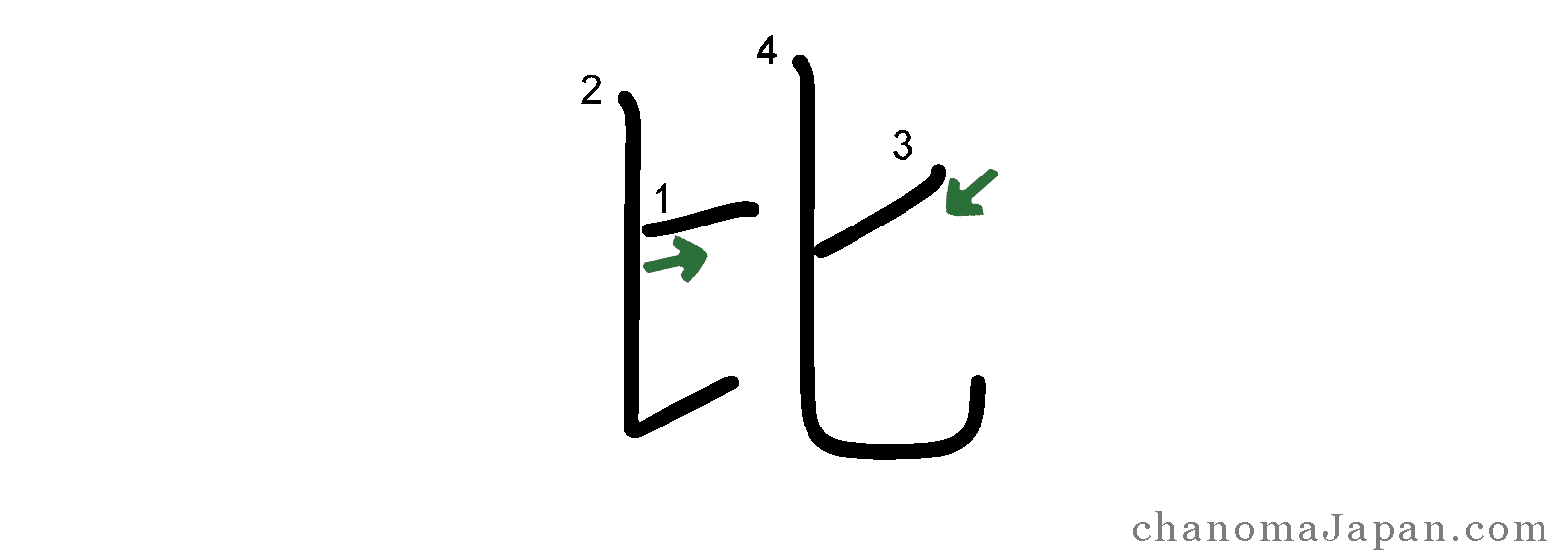

To conclude rule 10, let’s talk about a different shape: 比 kuraberu ‘to compare’.

The shape duplicated in the kanji 比 kuraberu ‘to compare’ is not an 卜 uranai shape. It represents a dead person: a corpse.

It would be easy to be deceived by the “long crack first” rule when writing this similar shape. Above I have reproduced this character as its stroke order is extremely counterintuitive. Notice how the direction of the shorter strokes is different between the first corpse shape and the second corpse shape.

That’s it! We have seen all ten stroke order rules. We can now move on to the structure of kanji.

Component Order (6 Rules)

CO rule 1: left to right

You’ve heard this a hundred times: left to right! But this time we apply the rule to the inner structure of a kanji, not the individual strokes.

Often kanji are made up of blocks of self-sufficient strokes, which are smaller components within a kanji. If you consider the kanji 林 hayashi ‘woods’, you should be able to identify two inner components: 木 ki ‘tree’, and then 木 ki again.

Component order rule 1 says that you should write the left-hand 木 ki first, and the right-hand 木 ki last.

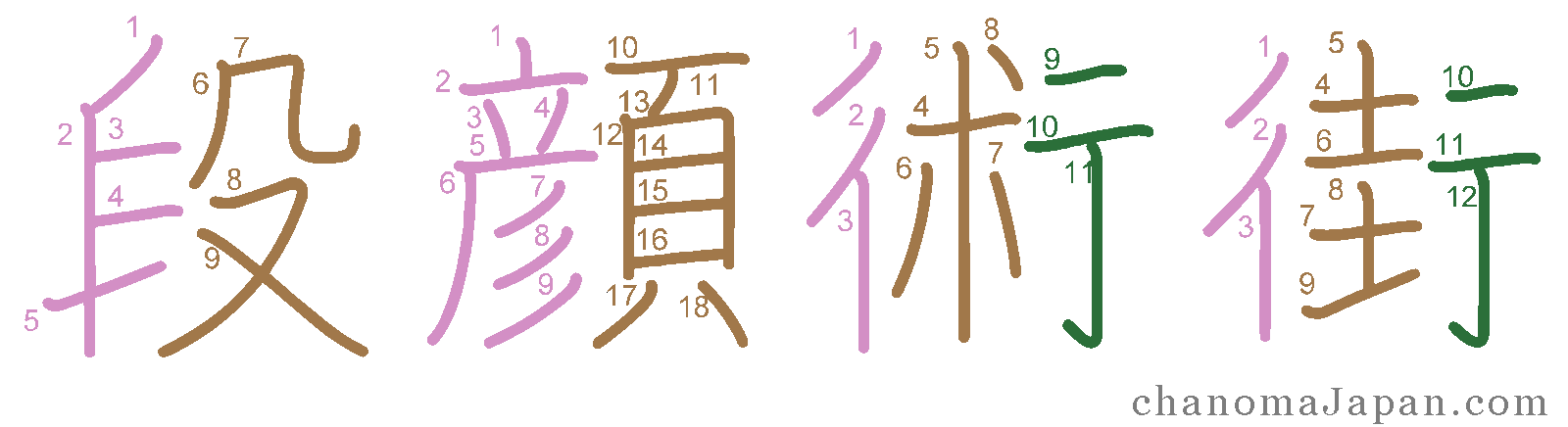

Let’s see our first component order diagram: 段 DAN ‘step’, 顔 kao ‘face’, 術 JUTSU ‘the art of’, 街 machi ‘town’.

Above, the red components are written first; the brown components second; the green components last. That is, left to right.

Take 段 DAN and 街 machi in the diagram above. Can you see how, in both kanji, the brown component can be split even further into smaller components?

The smaller components are: 几 ru, 又 mata and 土 tsuchi. In what order should we write them? The answer in the next section.

CO rule 2: top to bottom

The answer is: from the top to the bottom. We write the uppermost component first, then work our way towards the bottom.

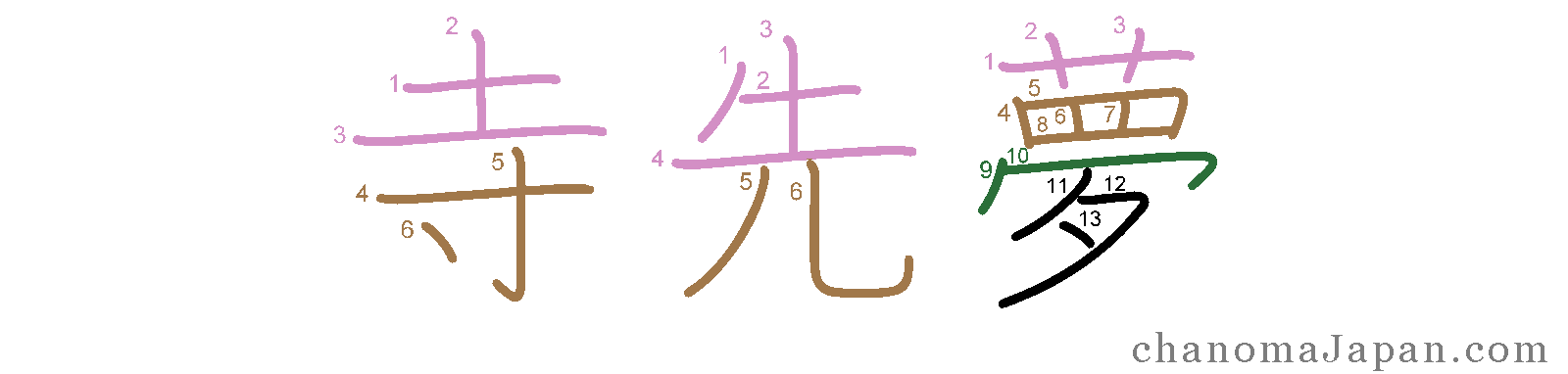

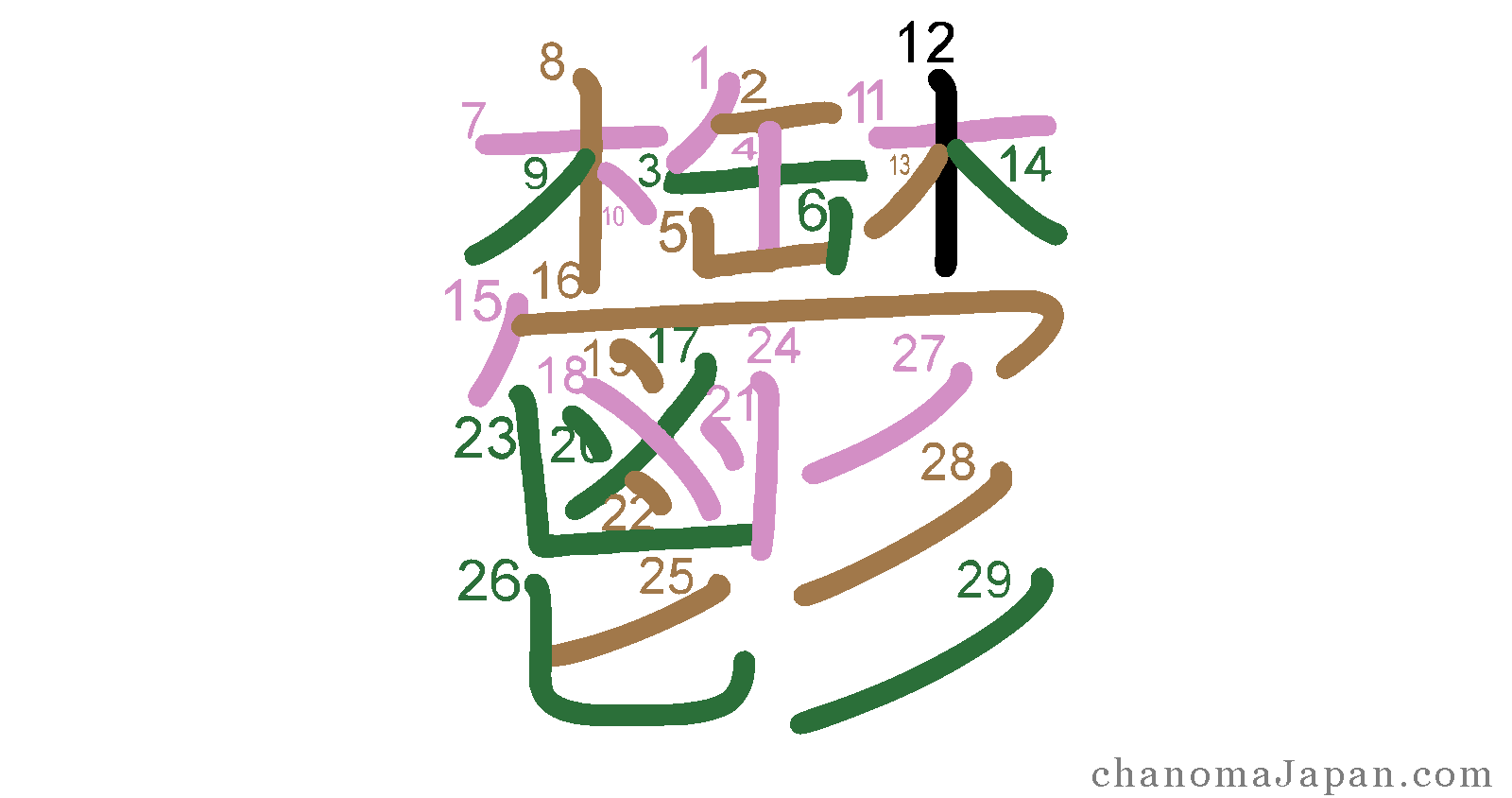

The components in 寺 tera ‘temple’, 先 saki ‘a point/tip’, 夢 yume ‘dream’ are shown in different colours. The order is: red, brown, green, black.

CO rules 1 & 2 combined

The left to right and top to bottom rules must work together.

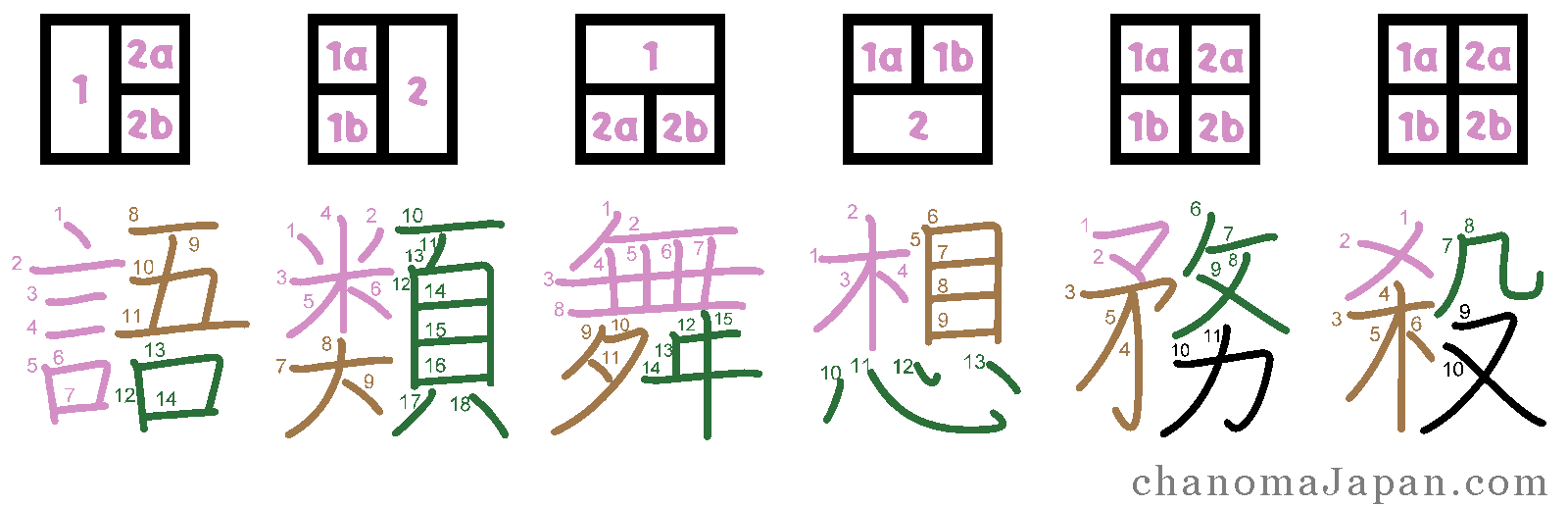

The image below presents four kanji with different internal structures. Their structures are represented in the square diagrams above the kanji.

The diagram shows what happens when the left to right and top to bottom rules are combined. The kanji are: 語 kataru ‘narrate’, 類 RUI ‘type’, 舞 mau ‘to dance’, 想 omou ‘to think about’, 務 tsutomeru ‘to serve’, 殺 korosu ‘to kill’.

Let’s focus on 語 kataru ‘to talk’: the implications for the remaining kanji are identical.

語 kataru has two inner components:

- 言 iu ‘to say’ and

- 吾 GO ‘I/myself’.

We can apply rule 1 (left to right) and write 言 iu first. Next we want to write 吾 GO.

But 吾 GO can be further subdivided into two inner components:

- 五 GO ‘five’ and

- 口 SAI ‘sacred vessel’.

We therefore apply rule 2 (top-to-bottom) and write 五 GO first, then 口 SAI.

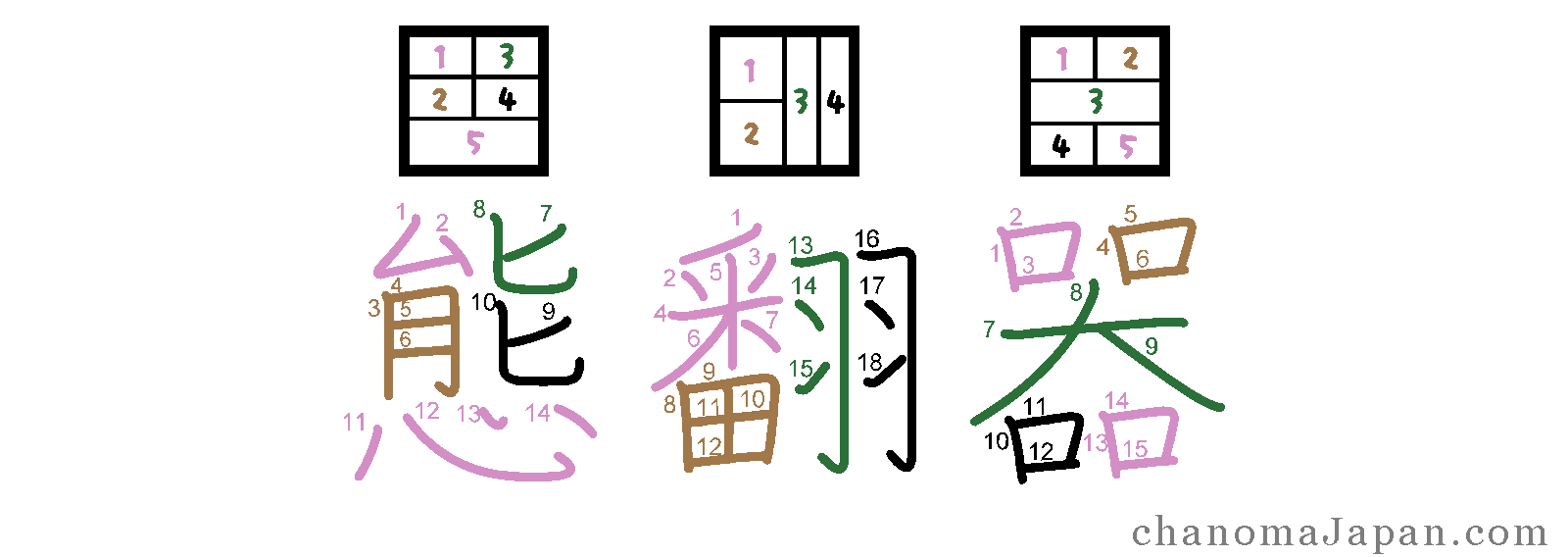

If you managed to wrap your head around this concept, you have then mastered the fundamentals of kanji structure and component order. Now I would like to increase the structure complexity just a little with the following examples: 態 TAI ‘condition’, 翻 hirugaesu ‘to flutter’, 器 utsuwa ‘vessel’.

The first character in the diagram is 態 TAI ‘condition’. It is made up with:

- ム mu,

- 月 tsuki,

- ヒ hi,

- ヒ hi,

- 心 kokoro.

Combined, the first four shapes constitute one macro-component, which exists as an independent kanji: 能 NŌ ‘ability’.

The fifth shape is the other macro-component, which also exists as an indipendent kanji: 心 kokoro ‘heart’.

能 NŌ can be split into a left sub-component and a right sub-component. Each sub-component can be further split into top and bottom components.

We then apply the rule recursively, until we resolve the component order of this kanji.

What we just learned covers the structure (component order) of the preponderant majority of the over 2000 kanji that constitute the basic Japanese script.

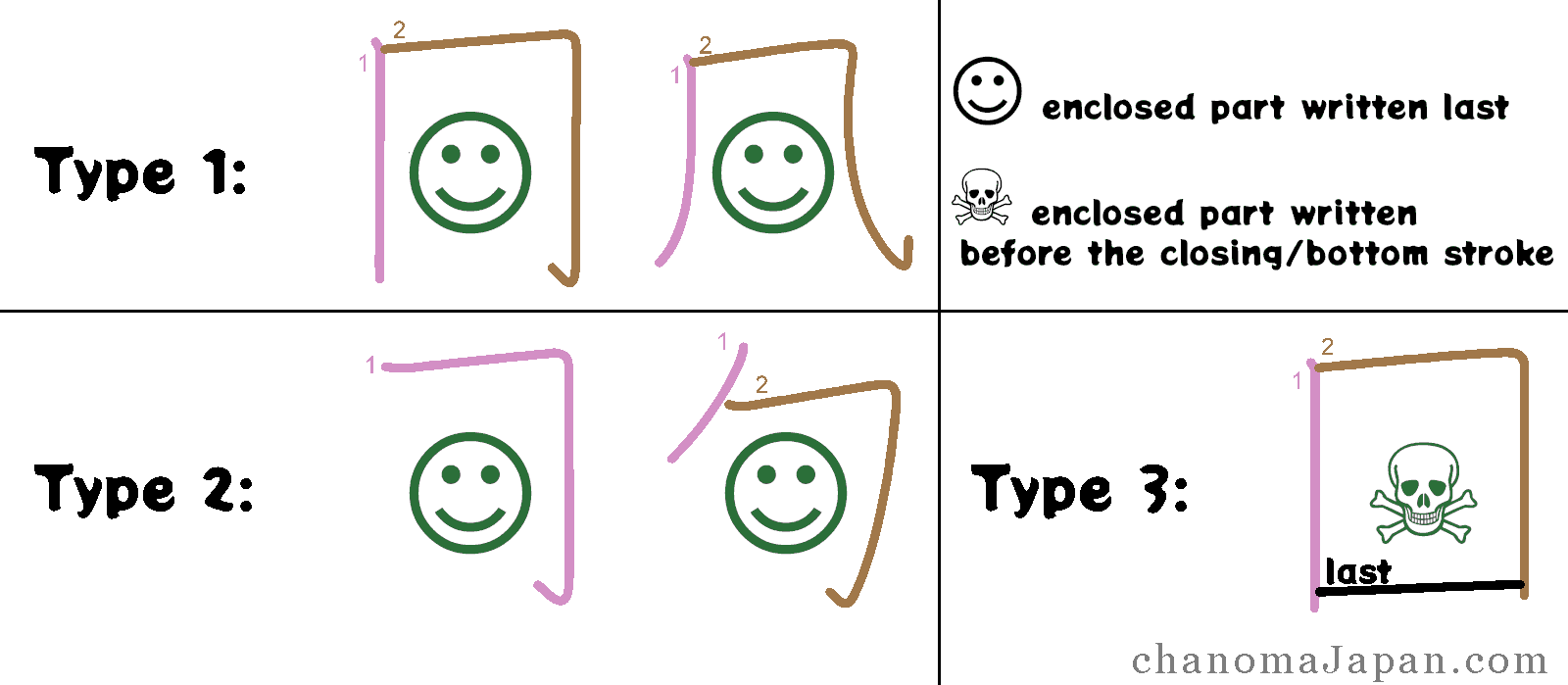

CO rule 3: embracing enclosures

Embracing enclosure are shapes that act like fences that surround, completely or partially, other shapes. Let’s start with the following three types of embracing enclosures: 冂 dōgamae, 勹 tsutsumigamae, 囗 kunigamae and other similar forms.

- Type 1: surrounding left, top and right.

- Type 2: surrounding top and right.

- Type 3: surrounding all directions.

The component order is as follows.

- Type 1: the enclosure is written first; the enclosed part last.

- Type 2: the enclosure is written first; the enclosed part last.

- Type 3: the left, top and right parts of the enclosure are written first; the enclosed part second; the closing/bottom stroke of the enclosure last.

Now we know how to write these kanji: 同 onaji ‘same’, 内 uchi ‘inside’, 風 kaze ‘wind’, 司 SHI ‘official’, 詞 SHI ‘word’, 句 KU ‘section’, 均 KIN ‘level/average’, 回 mawaru ‘rotate’, 国 kuni ‘country’, 園 sono ‘garden’.

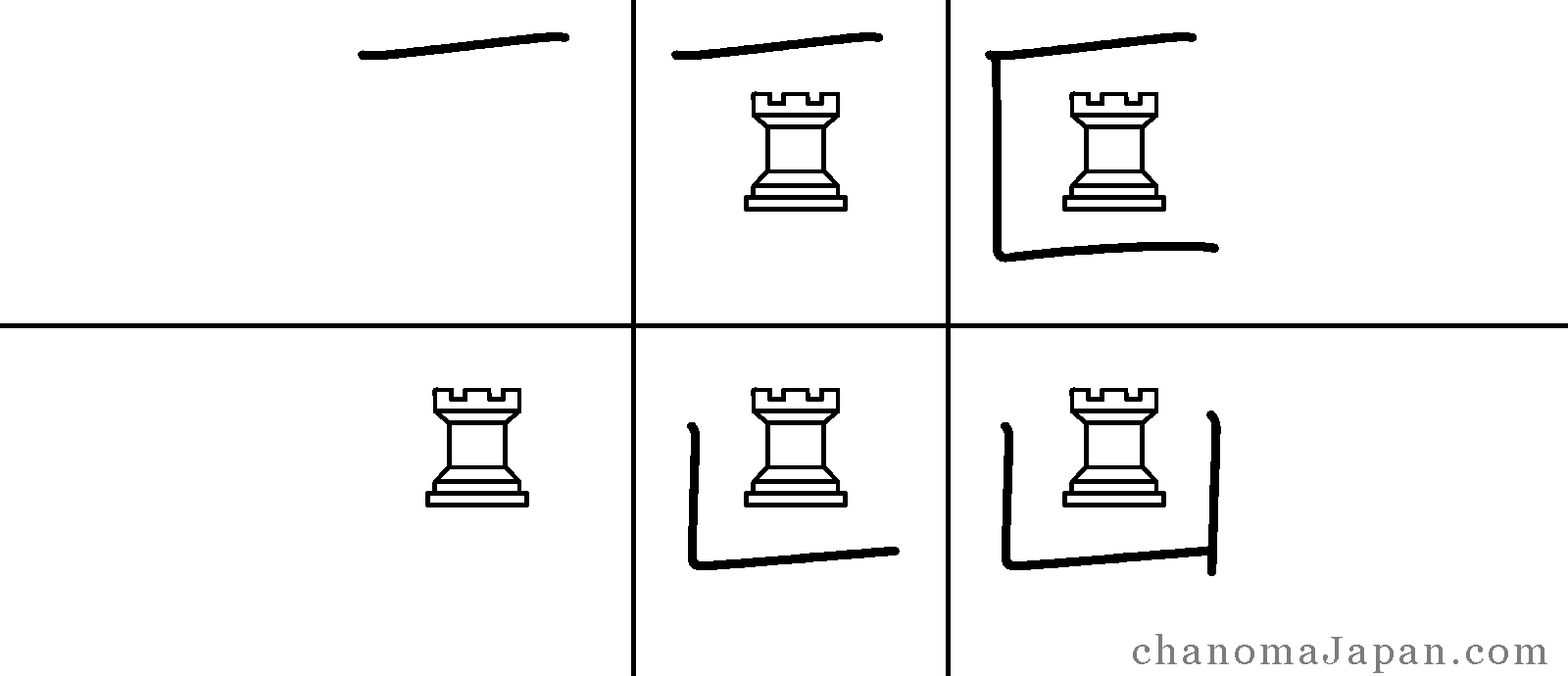

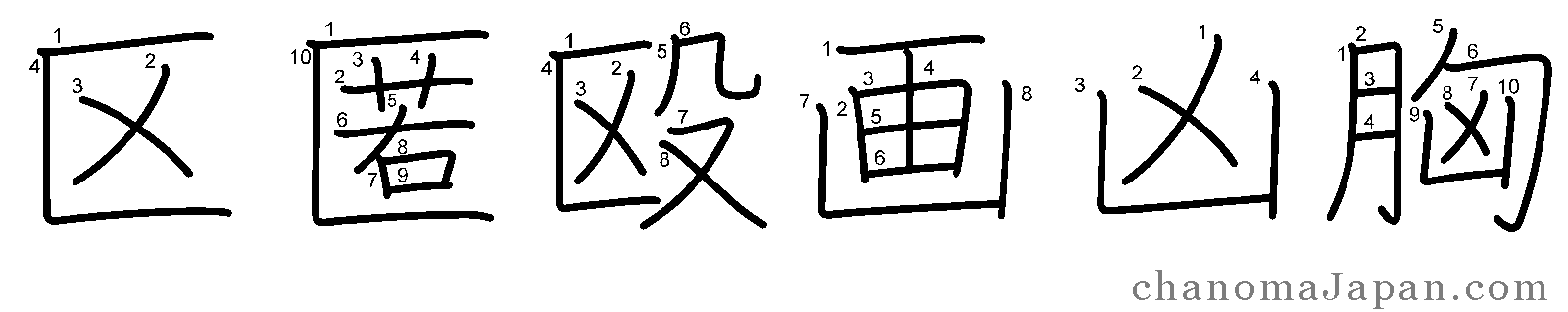

The next two embracing enclosures are 匚 hakogamae and 凵 ukebako.

The diagram should be self-explanatory, but let’s add two words to it.

- In 匚 hakogamae, the order is: top stroke; enclosed part; descending right-angled stroke.

- In 凵 ukebako, the order is: enclosed part; bottom right-angled stroke; right vertical stroke.

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, I’ll let the diagram below clarify any doubt with: 区 KU ‘ward’, 匿 TOKU ‘shelter’, 殴 naguru ‘hit/assault’, 画 GA ‘picture’, 凶 KYŌ ‘bad luck’, 胸 mune ‘chest’.

The last embracing enclosure that we are going to discuss is the 門 MON ‘gate’ shape, wich is a kanji on its own. A very common shape.

This enclosure is written first in its entirety; the enclosed part of the character is written last.

Some kanji with this enclosures are: 門 MON ‘gate’, 問 tou ‘to query’, 閣 KAKU ‘tower’, 閲 ETSU ‘inspection’, 開 hiraku ‘to open’, 潤 uruou ‘to be moist’.

Not an enclosure!

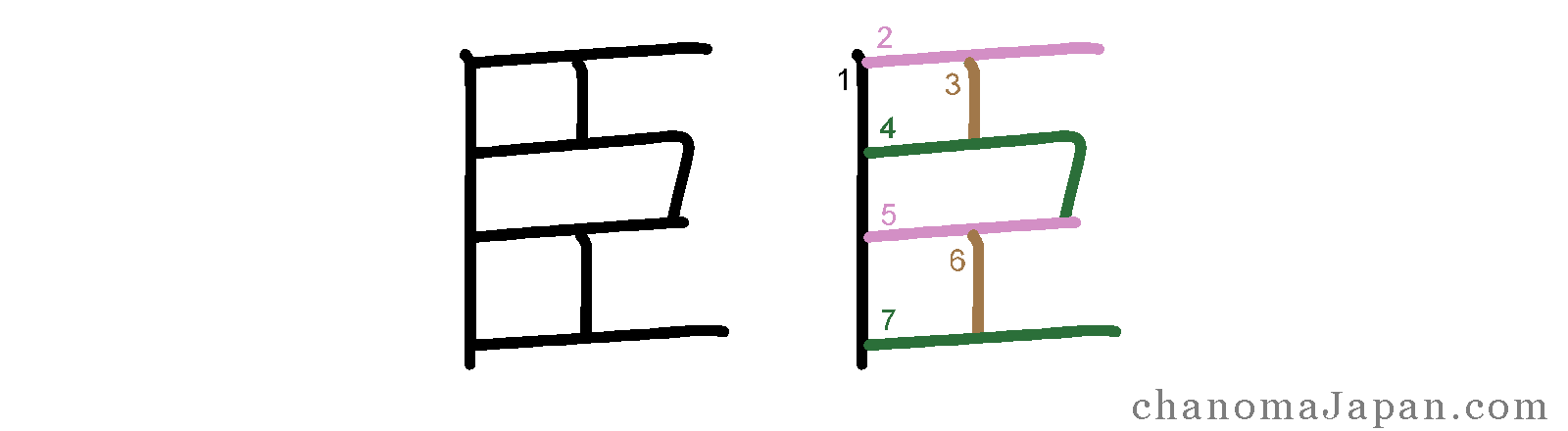

Let’s spend a few words on the shape/kanji 臣 SHIN ‘retainer’.

This shape is so confusing and deceiving that it deserves special mention.

What may look like a 匚 hakogamae enclosure is in fact something completely different. This whole thing is a single shape: the pictogram of an eyeball.

Lets find pen and paper and practice writing it!

CO rule 4: spear enclosures

Amongst all enclosures, spear enclosures are probably the most complex. Not only do they come in several different variations, but each enclosure, despite being a clearly defined kanji component, is rarely written in one go; instead, its stroke order usually “sandwiches” other components.

The reason I call them “spear enclosures” is that they derive from pictograms of actual spears.

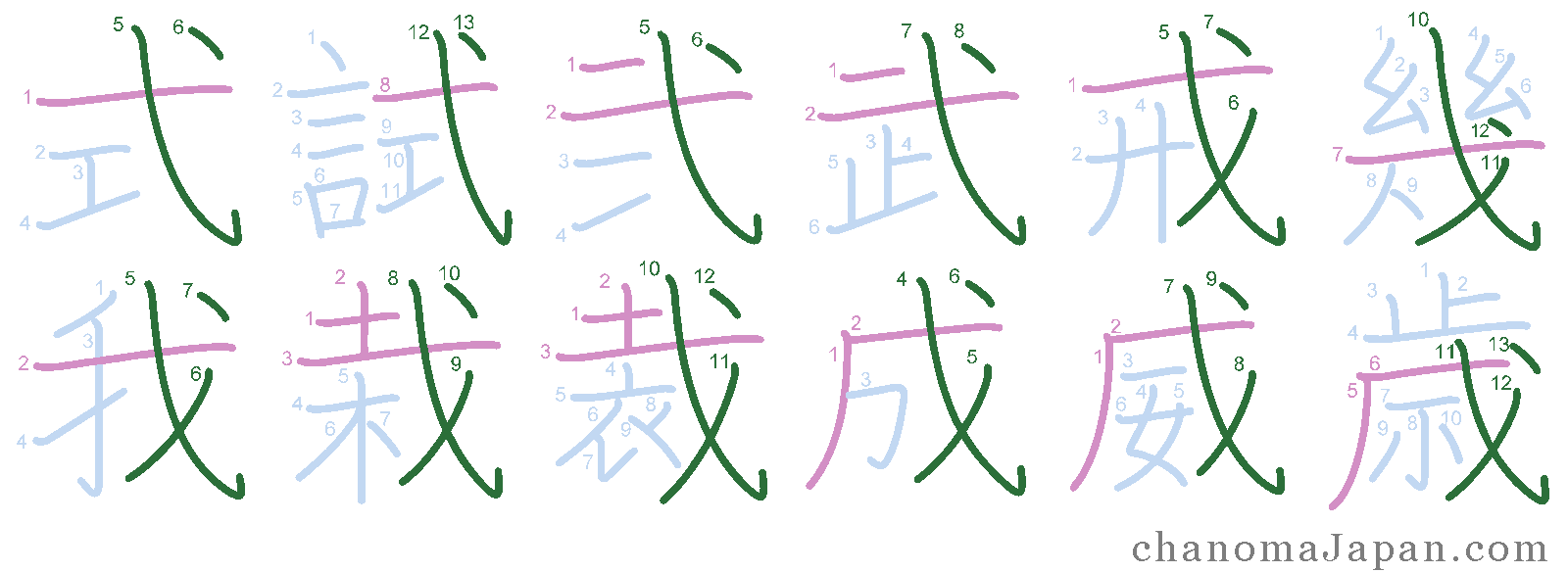

In the diagram you can see the six main spear enclosures that you will encounter as you study the 2136 常用漢字 jōyō kanji. They are 弋 shikigamae, 戈 hokogamae, and their variants.

When spear enclosure shapes are present within a kanji, the stroke sequence that you see above is interrupted, and other elements are written in between. Study the following diagram carefully, with the kanji: 式 SHIKI ‘system’, 試 tamesu ‘to attempt’, 弐 NI ‘two’, 武 BU ‘the art of war’, 戒 imashimeru ‘to admonish’, 幾 iku ‘how many’, 我 ware ‘myself’, 栽 SAI ‘to plant’, 裁 sabaku ‘to judge’, 成 naru ‘to become’, 威 I ‘authority’, 歳 SAI ‘years old’.

The component order is as follows:

- the part of the spear formed by the long horizontal stroke and related strokes is written first (red);

- the enclosed part is written second;

- the slanted part of the spear and related strokes is written last (green).

In the picture above 我 ware seems to be the only one not being perfectly regular, so pay particular attention to it.

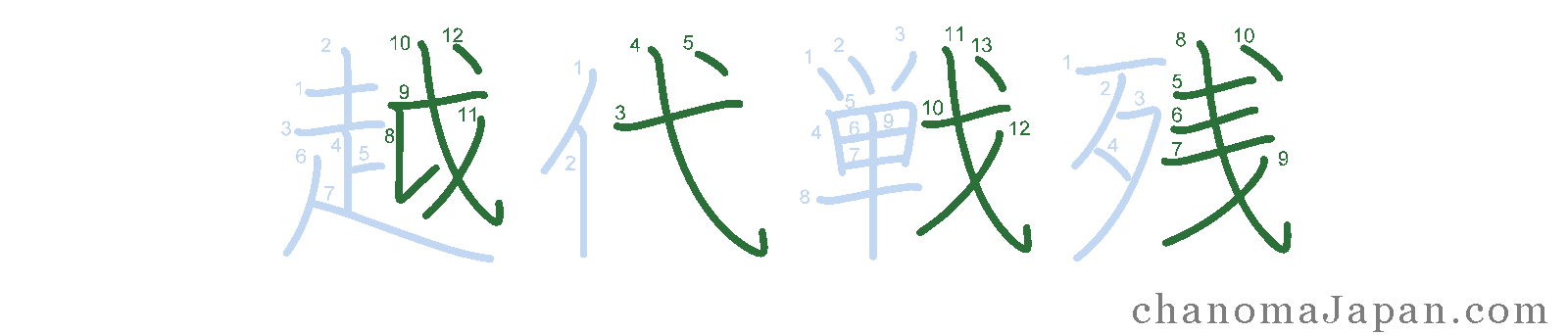

Moving on, sometimes these shapes are found as independent shapes, not acting as enclosures.

Eminent examples are 越 koeru ‘to surpass’, 代 kawaru ‘to replace’, 戦 ikusa ‘war’, 残 nokoru ‘to remain’.

CO rule 5: hanging enclosures

Hanging enclosures are always the first component to be written.

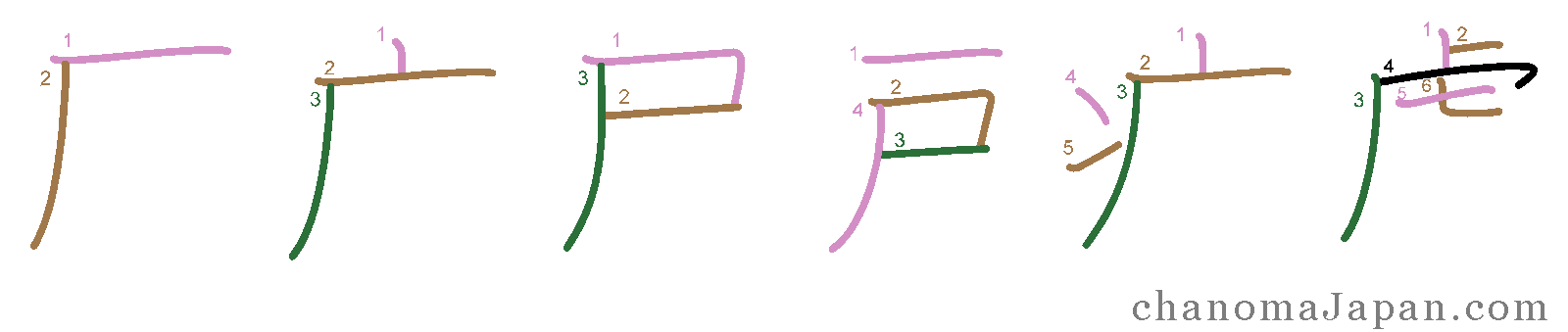

They are: 厂 gandare, 广 madare, 尸 shikabane, 戸 todare, 疒 yamaidare, 虍 toragashira.

虍 toragashira follows a very counterintuitive stroke order. I’ve seen university professors get this one wrong! The vertical slanted stroke is written before the hooked horizontal stroke (the roof of the hanging enclosure).

Above: 崖 gake ‘cliff’, 麻 asa ‘hemp’, 慰 nagusameru ‘to comfort’, 戻 modoru ‘to return’, 遍 amaneku ‘widely’, 病 yamai ‘illness’, 虎 tora ‘tiger’, 虜 RYO ‘prisoner’.

Within its respective shape, the hanging enclosure is written first, and the enclosed part is written next.

CO rule 6: sliding enclosures

These enclosures are normally called “lower-left enclosures”; I will call them “sliding enclosures” because of their vaguely slidy look.

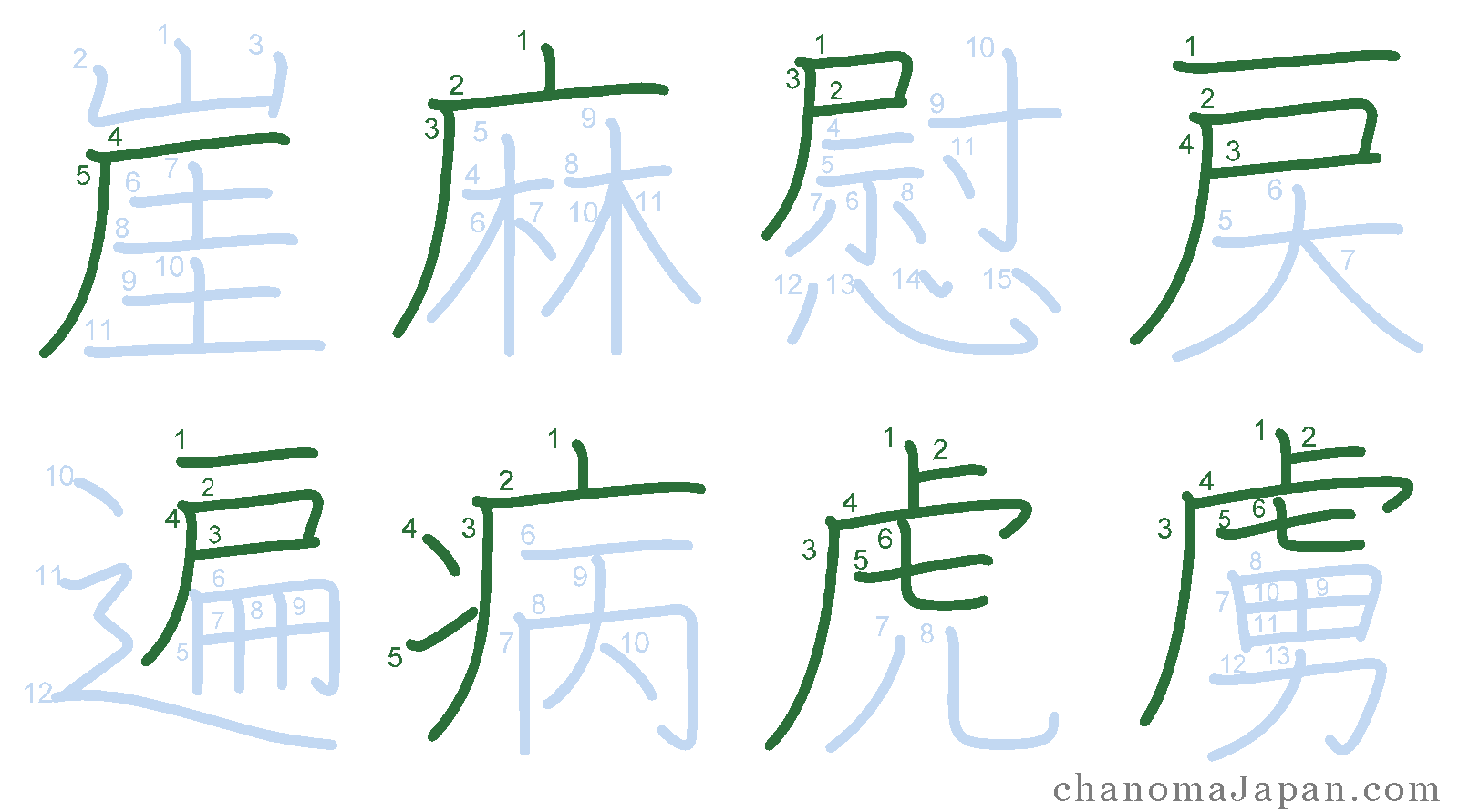

Some of the officially recognised sliding enclosures are: 夂 sui’nyō, 廴 ennyō, 走 sōnyō, 辶 shinnyō, 鬼 ki’nyō, 麦 baku’nyō. There are many more interesting shapes that we will see in this section.

There are two types of sliding enclosures:

- enclosures that are written first;

- enclosures that are written last.

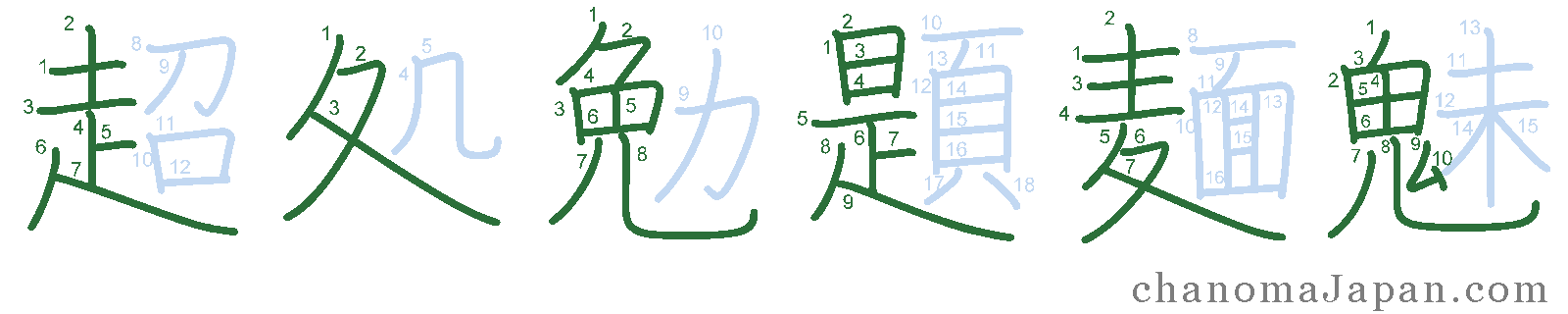

The sliding enclosure shapes in these kanji are always written first: 超 koeru ‘to surpass’, 処 SHO ‘to deal with’, 勉 tsutomeru ‘to endeavour’, 題 DAI ‘topic’, 麺 MEN ‘noodles’, 魅 MI ‘bewitch’.

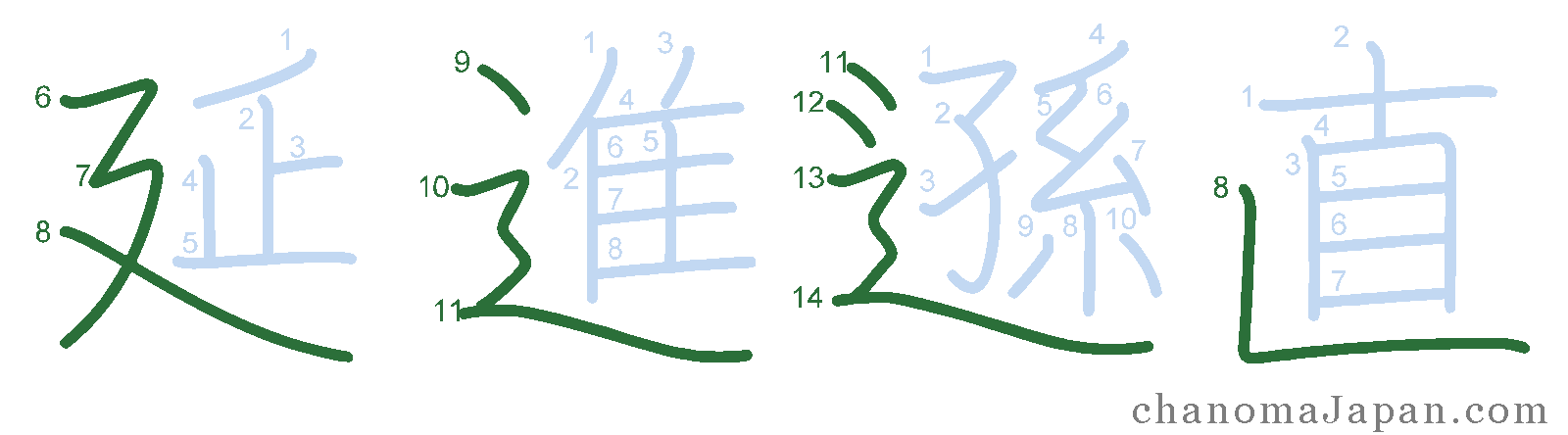

The sliding enclosure shapes in these kanji are always written last: 延 nobiru ‘to stretch’, 進 susumu ‘to advance’, 遜 SON ‘to abase oneself’, 直 CHOKU ‘direct’.

Difficult stroke orders

If you made it this far, congratulations. This is the final section of my Kanji Stroke Order Guide.

In the preface to this guide I said that, irrespective of your knowledge of specific kanji stroke/component order rules, it is best practice to always open a kanji dictionary to verify the correct writing. Nevertheless, a good knowledge of the rules listed in this guide will provide a good reference frame and help you speed up the memorisation process with a smaller effort.

It is for this reason that I want to present here a few of the:

- characters that don’t follow particular rules, and

- shapes that are unique or rare.

This will be a reminder that you should follow the best practice described above.

Study the stroke order of the characters in the following diagrams.

In the next diagram I listed some of the kanji with a stroke order that, for whatever reason, I found particularly difficult as I was studying kanji. I highlighted the difficulty in green where very localised. If there is no highlight, then the whole shape/kanji is somehow unpredictable.

In our last diagram: 鬱 UTSU ‘melancholy’. This is commonly believed to be the most complicated kanji to write.

This concludes our guide. I hope you found it useful!